Is it too soon to examine the White House of George W. Bush and Dick Cheney? Their tenancy is hardly ancient history, after all. We’re still mired in an unfunded war and struggling through a crippling financial crisis which both began on their watch. The plutocracy that they personified still rules American electoral politics and grows more powerful every Supreme Court term. And it will take decades to establish whether their overriding priority, a “global war on terror,” was an aberrational reaction to a temporary climate of shock and fear or the new, amoral chapter in world history they perceived.

Still, nearly all the key players have already weighed in with self-serving memoirs: both Bush and Cheney themselves and a warehouse pallet’s worth of others, including Donald Rumsfeld, Colin Powell, Condoleezza Rice, John Ashcroft, Paul Bremer, Tommy Franks, Karl Rove, George Tenet, John Bolton, Douglas Feith, Ari Fleischer, Paul O’Neill – even John Yoo, the lawyer who attempted a legal justification for our country’s use of physical torture on its “detainees” who had (and in some cases still have) yet to be charged with a crime. Of course, a memoir can only represent its author’s particular point of view, meaning only as much as the author can or cares to “remember.” What we need instead is a dispassionate narrative with no particular axe to grind, and here is the first one: DAYS OF FIRE by Peter Baker, the New York Times reporter who did a similarly non-judgmental job in THE BREACH, the definitive fly-on-the-wall account of Bill Clinton’s impeachment and trial.

If you have any presumptions about the two featured men, either as an admirer or a critic, you’ll likely find corroboration here, beginning on page 3, where Mr. Baker lays out the impressive Bush-Cheney record of accomplishment (if he’d done nothing else, Bush would still be the best friend Africa has ever had in the White House, one reason accusations of racism stung him so), and then in the following paragraph recounts the “misjudgments and misadventures” that “left them the most unpopular president and vice president in generations.” What impressed me throughout, though, was how the author was calmly able to disabuse me of some assumptions I personally held that just aren’t true.

George W. Bush is not an unintelligent man, though he’s aware that he can come across this way and over the years has found it useful as a bit of jujitsu against opponents: it gives him a negotiating advantage whenever he’s “misunderestimated.” Rather than dim, what he seems to be instead is incurious and impatient, probably after having lived a life that found its way down prescribed and predictable paths (with one notable exception). He has always had the benefit of mentors, friends, guides, some of them inherited. You can gauge your personal prejudice by considering the chilling five minutes on 9/11 after Andy Card told the president the country was under attack and he didn’t move from his chair in that Florida elementary-school classroom. Some will see a steely gaze on Bush’s face as he silently vows to bring the evildoers to justice. Others will note the same expression and see a man desperately hoping for somebody to tell him what to do. Mr. Baker suggests that Bush had thrived on, insisted on order, punctuality, and disruption-free schedules since he changed his life by giving up alcohol at age forty, and his temporary paralysis may have indicated he was coming to grips with the enormity of the desperate, uncontrolled, improvisational days to come.

Contrary to popular opinion, Dick Cheney was not Bush’s puppet master, and that was the notion which most rankled “the Decider” personally, particularly as he became more confident of his footing in the second term (to the eventual detriment of both Donald Rumsfeld and Scooter Libby). Cheney was certainly adept at behind-the-scenes manipulation, and served as the final gatekeeper regarding what the president saw on his desk, but none of Mr. Baker’s many sources can remember a single instance in which Cheney talked Bush into doing something against his will. Cheney’s genius was in understanding how Washington operates – most of it alien to his less experienced boss, even after having observed his father’s long federal career – and in encouraging inevitability. The perfect example was his own selection as vice president; as candidate Bush’s designated point man assigned to find a running mate (after first being asked if he would like to be considered himself), Cheney vetted nine potential veeps in such grinding detail that he possessed valuable information about each of them that precluded perfection in any of them. When the governor finally implored Cheney to run alongside him, the irony wasn’t lost on anyone. Dick Cheney had long said he’d love to be president if the job were simply handed to him; it was all the required baby-kissing and money-grubbing by the figurehead in an actual campaign that he disdained. Now, here was the closest anyone could ever get to that wish. Colleagues who served with Cheney as far back as the Nixon administration were later heard to mutter, this isn’t the Dick Cheney I thought I knew. But anyone who bothered to check his Congressional voting record, so radically conservative that it fit right in with early 21st-century smash-mouth Republicanism, wouldn’t have been so surprised. Except nobody did bother. Cheney, the great inquisitor, was himself never vetted as a V-P prospect. The job was simply handed to him.

Cheney was particularly attractive to Bush for another reason besides his long experience in government and business: uniquely among modern vice presidents, he did not aspire to the top job. As noted, he found running for national office odious, and that became doubly apparent during the campaign. There would be no sniping or second-guessing, no positioning or ass-covering for some future race. Halfway through the first term, Cheney mused aloud: “In this White House, there aren’t Cheney people versus Bush people. We’re all Bush people.” He was being overly generous to the president: of course there were Cheney people, led by chief of staff Scooter Libby and bulldoggish attorney David Addington, and his cadre quickly found itself at odds with the likes of Secretary of State Colin Powell and, less frequently, national security advisor Condoleezza Rice, particularly during the runup to Iraq. But as a potential competitor to the boss, Cheney didn’t compute at all – and Bush liked that, both as candidate and as president. The deference extended to official meetings: Cheney never opposed the president in public and tended to either keep silent or ask an occasional question. They held private weekly lunches, but all we know about them is what they told us or their aides.

Having served in the Nixon administration and as President Gerald Ford’s chief of staff before being elected to Congress, Cheney witnessed firsthand what he felt to be a dangerous swing of the pendulum of power from the Presidency toward the legislature – an overreaction, in his view, to the Watergate scandals. When it came to authority, Cheney was a Nixonian (“When the President does it, that means that it is not illegal”) and felt no more need to “ask permission” for extraordinary rendition and CIA black-ops than Ronald Reagan had for the Iran-Contra affair. Cheney’s world was black and white, populated by heroes and villains, and from this he never wavered during all his years in office.

Conventional wisdom about the self-described “compassionate conservative” was that George W. Bush was basically a nice guy who got in over his head, but that isn’t accurate either. It’s a notion held over from his fairly successful service as Texas governor, a constitutionally weak position in which he was forced to work alongside Democrats in the state legislature. But family observers had long noted that Bush personally took after his tough, no-prisoners mother over his more conciliatory father. He had been the senior Bush’s doctrinaire enforcer and hatchet man during the 1992 campaign; it was George W. who informed chief of staff John Sununu that he should resign. Upon losing the popular vote and gaining the presidency by its fingertips when a Florida recount was halted in a highly controversial 5-4 Supreme Court decision, the Bush administration – particularly in the form of Cheney – proceeded to govern as if it had won a landslide. There would be no compromise, divided electorate or not. Advisor Karl Rove, who comes off in this account more important in his own mind than he is to day-to-day governance once the elections are done, famously admitted as much early in the first term: it doesn’t matter how close the margin, just as long as you win. The first concrete indication that these people weren’t all that compassionate was a private-sector task force convened by Cheney a few months after inauguration to advise on federal energy policy: not only were outsiders barred from the meetings and their conclusions, we weren’t even allowed to know who had attended. One name appearing on everybody’s speculative list was the doomed Enron’s doomed Kenneth Lay, whom Bush affectionately called “Kenny Boy.” But we don’t know for sure. Transparency was for wimps.

One thing the satirists did get right was Bush’s tendency to receive a first impression and then stick with it, to “go with his gut.” He “loathed” Kim Jong Il of North Korea, but after meeting Vladimir Putin, pronounced him “honest, straightforward.” “I looked the man in the eye,” said Bush, and “I was able to get a sense of his soul.” When Cheney looked Putin in the eye, he thought, KGB, KGB, KGB. Unlike the hard-charging 1992 campaign worker, the presidential Bush was more likely to shy away from personal conflict. He hated firing people, particularly those who had been loyal to him. When Attorney General Alberto Gonzales’s head came on the block, he insisted on a personal meeting, and only after a reluctantly hosted and uncomfortable lunch at Bush’s Texas ranch did it become clear to the General that longtime fealty was no longer a basis for appeal.

Bush’s complicated relationship with his father almost surely colored his entire presidency, partly in ways we’ll never understand. For most of George W.’s pre-political life, it was his industrious younger brother Jeb of whom their parents expected great things; the eldest son was wasting himself in frivolity and desultory attempts at business. It was a strange inversion of the Kennedy family history, in which golden boy Joe Jr. self-abdicated in a premature WWII bomb explosion, and younger freewheeling playboy Jack ascended to the Senate and presidency instead. When George W. Bush sobered up in 1986, he was still the “black sheep” of the clan, and he had lots to prove, both to his father and to himself. When he unexpectedly beat Ann Richards in the 1994 Texas gubernatorial race on the same night that Jeb lost his first election for Florida governor, Bush asked his father over the phone, “Why do you feel bad about Jeb? Why don’t you feel good about me?”

There were two main lessons “43” took from “41”’s presidency. First, breaking the elder Bush’s famous “read my lips: no new taxes” pledge cut him off at the knees among hard-line conservatives, who use a Mad Hatter-like formulation regarding taxes and the economy. If there’s a deficit, businesses are being taxed too heavily and are disinclined to hire and grow. If there’s a surplus, as “43” inherited from President Clinton, then taxes are still too high because the government is taking in more than it spends. (Never mind the national debt; that only clouds the issue. As Cheney said one day, “Reagan proved deficits don’t matter.” That is, unless a Democrat is in the White House.) “This is not only no new taxes,” Bush proclaimed during a January 2000 debate. “This is tax cuts so help me God.” He made good on his promise barely four months into office.

The second lesson emerged only in retrospect. When the Persian Gulf War liberated Kuwait from Saddam Hussein’s army in February 1991, “41”’s popularity was the highest of his presidency: even Democrats approved of his performance by a four-to-one margin. He looked unbeatable for re-election. But less than two years later, he was defeated by a deteriorating economy and the Clinton campaign’s unerring focus on it. The tax issue was probably the dealbreaker, but “43” and Cheney detected another chink in the armor: with the world’s most powerful ground force deployed only kilometers away, “41” had not completed the job by deposing Hussein with military muscle. There were many good reasons to simply accomplish the stated mission and leave, which is exactly what happened, but Bush and Cheney felt Saddam had only been emboldened to continue terrorizing his people and developing nukes. A disrupted 1993 car-bomb plot to assassinate Kuwait’s emir and “41,” purportedly traced back to Saddam, was a particular burr. “After all, this is the guy who tried to kill my dad,” Bush said at a 2002 fundraiser. If generals had seized the day and marched on Baghdad, that might never have happened. At one of their weekly lunches, as Bush was wrestling with the decision to extend his own war into Iraq, Cheney even goaded him on a personal level, one cowboy to another: “Are you going to take care of this guy or not?” Years later, Bush was surprised that this bit of impertinence had stuck with him, but it had its effect at the time.

After 9/11, the notion of retaliation against Iraq had surfaced almost instantly, beginning with Bush himself. “See if Saddam did this. See if he’s linked in any way,” he ordered counterterrorism chief Richard Clarke. “But Mr. President, Al-Qaeda did this.” “I know, I know, but see if Saddam was involved. Just look. I want to know any shred.” (As events later proved, he wasn’t kidding about the shreds.) The first few hours after the planes struck were chaotic, with the president struggling to get back from Florida while buildings were burning in New York and D.C. As United Airlines Flight 93 sped toward Washington, Cheney ordered it shot down – and twice more as a military aide re-confirmed “authority to engage.” Recollections differ as to whether he had obtained Presidential approval in advance, but “none of about a dozen sets of logs and notes kept that day recorded the call,” writes Mr. Baker. The plane was brought down instead in a Pennsylvania field by its passengers, before any Cheney order was given (and, fortunately, ignored), as frantic cell-phone calls revealed that other airliners were being used as deadly missiles. Most observers speculate its target was the Capitol or the White House; Cheney and team were below the East Wing in a secure but “low-tech” bunker that had never been used in a crisis before. Cheney spent most of the next few weeks at one or another “secure undisclosed location” (his own words) in order to maintain the line of succession in case of further attacks. Usually the secret hideout was no more exotic than Camp David or his own residence, but it was still undisclosed.

Bolstered by an historic wartime thumbs-up from the electorate – not dissimilar to Bush’s father’s – which extended into the 2002 midterms, Bush and Cheney might possibly be forgiven for convincing themselves that they were acting on behalf of a united nation. To the “reality-based community” (a notorious term that came from an anonymous Bushie widely believed to be Karl Rove), however, the administration needed to pound into “truth” the notion that Saddam Hussein possessed weapons of mass destruction. (Never mind that another member of Bush’s “Axis of Evil,” North Korea, actually had nukes.) Some suspected the actual motives were less noble after watching post-invasion Iraqi looters sack everything in sight – including museums and munitions dumps – except for the one bit of infrastructure under Coalition protection: the oil fields.

“Stuff happens,” shrugged Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld at one of the press conferences that made him something of a rock star after the invasion proved easier than anybody expected. Saddam’s army quickly dissolved away, allowing a cathartic “victory” to play out on American tv sets tuned to the “shock and awe” channels, and it turned out that Iraq had actually long since disposed of its WMDs but maintained enough of a pretense to juice the dictator’s perceived international importance and keep the hated Iran at bay. Rumsfeld is the subject of Errol Morris’s new film THE UNKNOWN KNOWN, which one might expect to be a companion to his Oscar-winning THE FOG OF WAR (2003), in which former SecDef Robert S. McNamara expresses second thoughts (his “eleven lessons”) about our prosecution of the Vietnam war. But Rumsfeld displays no contrition, no beard-stroking, no doubt whatsoever. In this he was typical of the Bush inner circle.

Without Donald Rumsfeld, you might not even have a Dick Cheney. It was Rumsfeld, Cheney’s longtime mentor, who convinced President Ford to bring Cheney in to succeed him as Chief of Staff when he became the youngest man ever to serve as Secretary of Defense. Cheney returned the favor years later when he counseled Bush to appoint Rumsfeld as the oldest SecDef in history. Through all the intramural squabbles of the Bush years, Cheney and Rumsfeld were never on separate teams. Rumsfeld was the ultimate organization man, highly attuned to protocol and what he saw as proper chains of command. He communicated orders and random thoughts in hundreds of memos that were so voluminous they came to be known by his staff as “snowflakes.” Rumsfeld spends much of THE UNKNOWN KNOWN reading from various snowflakes, some of which sound like koans, full of Zen ambiguity but lacking any enlightenment. For example, this passage, which originated as a press conference answer and gives the film its title: Reports that say there’s — that something hasn’t happened are always interesting to me, because as we know, there are known knowns; there are things that we know that we know. We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns, the ones we don’t know we don’t know. One Rumsfeld snowflake was directed at President Bush as he searched in vain for WMDs in Iraq: Absence of evidence is not evidence of absence. By such logic did our country invade a sovereign nation in a runup so blind and frantic that besides squandering precious blood and fortune, it also consumed the political career of a man who otherwise might well have become the first black president of the United States: General Colin Powell. (Think about how that might have altered the Republican brand.)

In Rumsfeld’s view, SecDef’s job was to wage and win a war. Whatever happened afterward was somebody else’s responsibility. In fact, the various administration members’ accounts of the post-invasion debacle form a Quentin Tarantino-like Mexican standoff, pointing at each other with fingers rather than pistols. What fool dissolved the Iraqi army, encouraging trained soldiers to fade back into the population as armed dissidents? Who failed to protect storehouses of weapons and ammunition, never mind priceless, irreplaceable cultural antiquities? How did uniformed American jailers turn into sadistic monsters? When did we begin fighting wars with contractors and mercenaries, including a private-sector paramilitary immune from U.S. or Iraqi law? What gave us the idea that we could pay for this whole mess with another country’s oil? Each memoirist tells us, in his or her own way: I don’t know, bro, but it sure wasn’t my fault.

Rumsfeld held a great advantage over Bush, at least while war plans were being laid. To his fellow Texan, Lyndon Johnson’s tragic mistake in Vietnam was trying to micromanage the war from Washington. Bill Clinton, to some extent, had been guilty of the same thing in tentative humanitarian uses of the military (even though Clinton had worked his will in Kosovo without a single casualty). Instead, Bush resolved to listen to his generals on the ground, under the direction of Rumsfeld. The only general he didn’t listen to was Army chief of staff Eric Shinseki, who told the Senate Armed Services Committee that “several hundred thousand soldiers” might be needed to occupy Iraq after the war, in direct opposition to Rumsfeld’s notion of a quick, sleek, in-and-out strike by a lean, techno-savvy force. Shinseki was never asked to elaborate, and was replaced later in the year.

The speedy ground “victory,” and Bush’s “Mission Accomplished” football-spike aboard the USS Abraham Lincoln, kept the wartime fervor bubbling hot enough to defeat Sen. John Kerry and win a second term. Bush liked to brag that more people voted for him than for any other presidential candidate in history. (The all-time #2? Sen. John Kerry in that same election. It helps when there’s no vote-siphoning from a third-party candidate, as Ross Perot did to “41” and Ralph Nader did to Al Gore. Both were topped by Barack Obama four years later, but Bush is still the only Republican presidential candidate to win the popular vote since his father in 1988.) Re-energized, vastly relieved at never having to campaign again, emboldened by a victory that was clearly mathematical after the overly lawyerly 2000 race, and much more comfortable in his presidential skin, Bush enthused in his first post-election press conference: “I earned capital in this campaign, political capital. And now I intend to spend it.”

But now the war had entered its excruciating just-dragging-on phase, a bloody grind of noise behind anything else the president tried to accomplish. He had some plans for the second term, to at least partially privatize Social Security and forge some desperately needed immigration reform. But the public was losing patience with the war effort and thus its authors. Sovereignty had been handed over to Iraq (“Let freedom reign!” Bush scribbled on Condi Rice’s note. Not “ring.” Reign.), but without U.S. troops it only amounted to a few words on a piece of paper. The lurid images from Abu Ghraib prison had been assimilated but not forgotten. Don Rumsfeld had gallantly offered his resignation over the scandal, but as Mr. Baker writes, “cynically, it could be seen as forcing Bush to either support him or cut him loose.” “Pretty smooth,” Bush told an advisor. “He called my hand.”

That had been the first-term Bush. The more assured second-term president now paid less attention to the likes of Cheney and Rumsfeld; one imagines he must have been growing tired of advice that the fullness of time was proving so wrong. There’s a famous clip, used by Michael Moore in his film FAHRENHEIT 9/11, of Bush resolving to hunt down America’s enemies, then stepping back to a golf tee and saying, “Now watch this drive.” It makes him seem callous, flippant, even foppish (whatever PR officer approved that idiotic photo-op should have been beheaded), but that’s not so, either. Bush agonized over the victims of his wars, at least on the American side, and his frequent visitations and other acts of kindness to veterans and their families went unpublicized, which suggests to me that they were genuine. (He even temporarily gave up golf in sympathy, perhaps because of that mortifying clip.) The war consumed Bush, and if any regrets were deeply internalized – you can’t betray your troops by second-guessing their mission, he frequently said out loud – they were still present.

Despite Rumsfeld’s space-age cogitations, it appeared that what we really needed was more troops (easier to argue than more domestic spending, which we needed as well), and with the support of the usual suspects – John McCain has never seen a military muster he didn’t like, and his obviously bobbleheaded choice of Sarah Palin later helped our nation dodge a fusillade of bullets because he could only grouse from the Senate, not push buttons from the Oval Office – Bush doubled down on the troops a la Shinseki and thus helped tamp the reddest Iraqi embers. When I heard Citizen Rumsfeld’s Fox News comment two months ago that, in his words, “a trained ape” could have done a better job handling Afghanistan’s President Hamid Karzai than President Obama and his team, I first wondered how the word “ape” came to mind, then reminded myself that I shall never again be lectured on foreign policy by this particular individual. As for Cheney, Mr. Baker writes that by the time of the surge, “He was becoming more like a regular vice president.” In June 2007, when Cheney urged bombing of Syria’s newly discovered nuclear reactor at a meeting of the national security team, Bush asked, “Does anyone here agree with the vice president?” Not a single hand went up.

When Bushies were delivered their electoral “thumpin’” by a war-weary electorate in the 2006 midterms, it was finally time for Rumsfeld to go away for good, and the chief picked up SecDef’s longstanding offer of resignation like a Texas-League grounder. (Some Republicans, who were beginning to recognize a sinking ship when they saw one, began grousing that if Bush had thrown Rumsfeld to the dogs before the election, it might have helped their chances, but to Bush that would have been a sign of weakness, always less desirable than wrongheadedness.) This did not sit well with Cheney, but less and less did these days; if the president was a lame duck, then what did that make a vice-president who was not interested in running for higher office? The debilitating ennui of the war, now officially America’s longest, topped by a financial cataclysm overseen by the “business party” (i.e., the foxes had been guarding the henhouse all along) rendered McCain’s ticket – made to appear even more feckless by the transparent Hail-Mary selection of Gov. Palin and his tin-eared insistence on a money-meltdown White House “summit” at which he barely spoke – DOA against the first credible black candidate in history, who was only there because he’d narrowly beaten the first credible female candidate in history. On the way out, Bush even towel-snapped Cheney one last time by refusing to pardon the veep’s loyal aide Scooter Libby, who had been convicted of leaking the name of a covert CIA officer. He commuted Libby’s sentence, obviating jail time, but refused to wipe the slate clean, despite all of Cheney’s protestations right up to Inauguration Day. Bush was his own man on this issue, and if he had not always been, perhaps he had grown in the office. At least when measured against Dick Cheney.

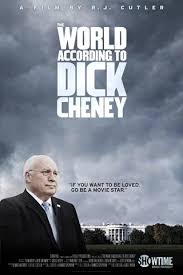

Cheney was nothing if not stalwart. He became obsessed with the possibility of another attack against America, a “second wave,” and he never let it go. As with the Commies he hated, to him the end justified the means, thus “extraordinary rendition” and “enhanced interrogation techniques,” his cold-blooded euphemisms for US-sponsored extra-legal kidnapping and torture. He famously held that “if there’s a 1% chance that Pakistani scientists are helping al-Queda build or develop a nuclear weapon, we have to treat it as a certainty in terms of our response.” Cheney’s “One Percent Doctrine” applied only to 9/11, not the 95% of scientists alarmed over man’s contribution to climate change or the 90% of Americans who favored stricter gun regulations. He continued to insist, notably in R. J. Cutler’s 2013 film THE WORLD ACCORDING TO DICK CHENEY, that he had protected America against further attack and foiled evil plots due to information gleaned extraordinarily, though some interrogators say they obtained every bit of actionable stuff without resorting to torture.

Bush admired Barack Obama’s meteoric rise but felt his successor was unqualified to prosecute American foreign policy, perhaps forgetting his own global inadequacies on Inauguration Day 2001. When candidate Obama remarked in a debate that he would send U.S. forces into Pakistan to chase terrorists even without the government’s permission, Bush found it “stunning” in its “naivete.” (That Cheneyesque bit of bravado, of course, was exactly how Obama eliminated Osama bin Laden, an accomplishment that had eluded Bush for seven years.) “This guy has no clue, I promise you,” Bush ranted one day. “You think I wasn’t qualified? I was qualified.”

Near the end of his term, a former aide asked Bush, “You’re leaving as one of the most unpopular presidents ever. How does that feel?” Bush responded, accurately, “I was also the most popular president.” After 9/11, his approval rating reached 90%, the highest ever recorded. But his fall from public grace was also historic. During the nadir of the financial crisis in October 2008, a Gallup poll found that 71% of Americans disapproved of Bush’s job performance, the lowest marks for any president since the firm began asking that question in 1938. And while others at their worst – Nixon, Truman – fell below Bush’s low approval ratings, his dragged on and on. The last time a majority supported Bush was March 2005, “meaning he went through virtually his entire second term without most of the public behind him,” as Mr. Baker writes, and Cheney fared even worse. But “Bush’s graceful post-presidency seemed to temper judgments.” Unlike Cheney, unlike Rumsfeld, unlike nearly everyone else in his administration, Bush has found the fortitude to resist self-indulgence. In retirement he has uniquely been able to maintain a discreet silence, and his legacy is at least partially mending as he displays the common courtesy that few others in his party can manage to conjure.

Wow, what a comprehensive review! I feel like I don’t even need to read the book, although from what I could tell, it sounds uncannily accurate. I was not a fan of the Bush Administration, not at all, but reading this post has made me re-think some of my snap judgments. It’s kind of funny; I always thought Bush was a terrible President, but probably a fairly decent man. Just goes to show that one’s ability to remain “discreet” does not necessarily make one a great leader.

LikeLike