If you like movies, you’ll periodically be delighted, surprised, tickled, thrilled, even amazed at the talent of the people who put them together. But only twice in my life have I walked out of a screening absolutely gobsmacked — emotionally flattened, finding it difficult to fully process what I’d just seen. The first happened just about this time of year exactly half a century ago, when some friends and I first saw 2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY.

A carload of college chums drove from Jackson, Mississippi to New Orleans — a three-hourish trip — to the Martin Cinerama, for 2001’s original 70mm “road show” engagement. We saw the movie and then we drove three more hours back (we collegians hadn’t enough dough for anything else). But that return trip was almost completely devoted to awed conversation which is most accurately rendered as: “Holy shit!” In other words: minds blown, it was frickin worth it.

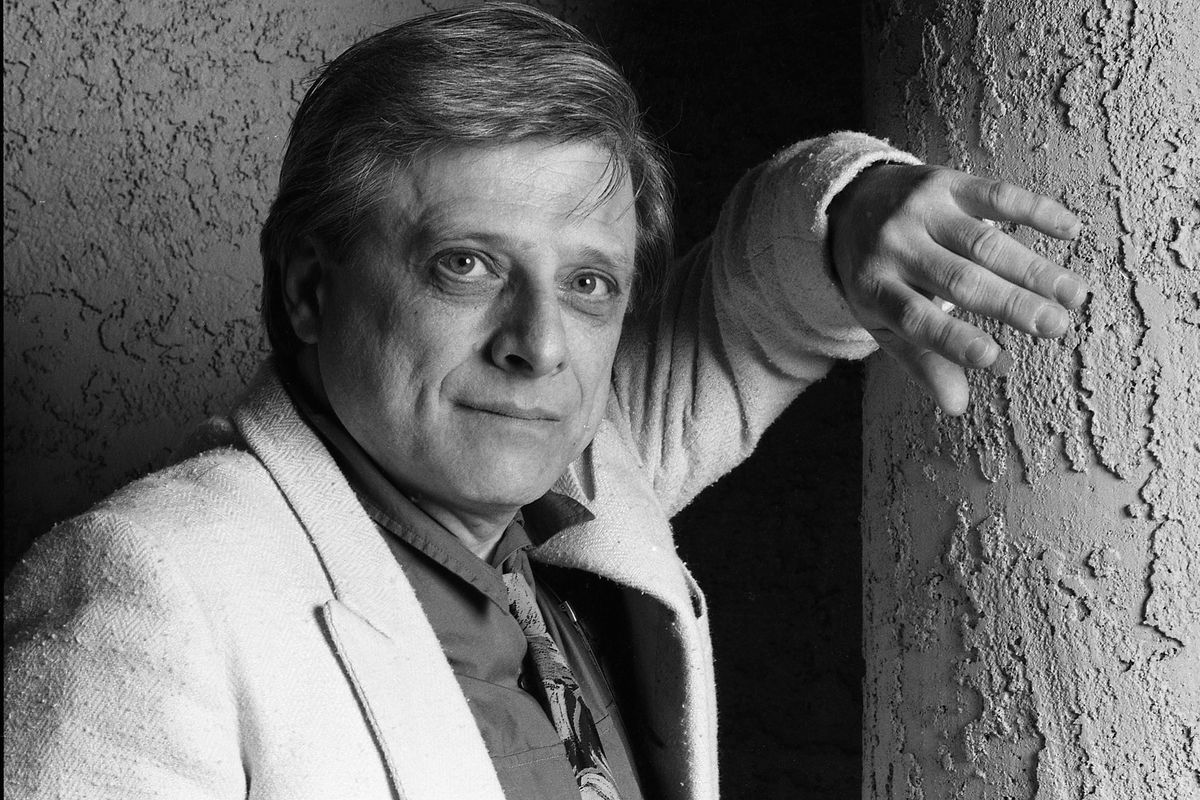

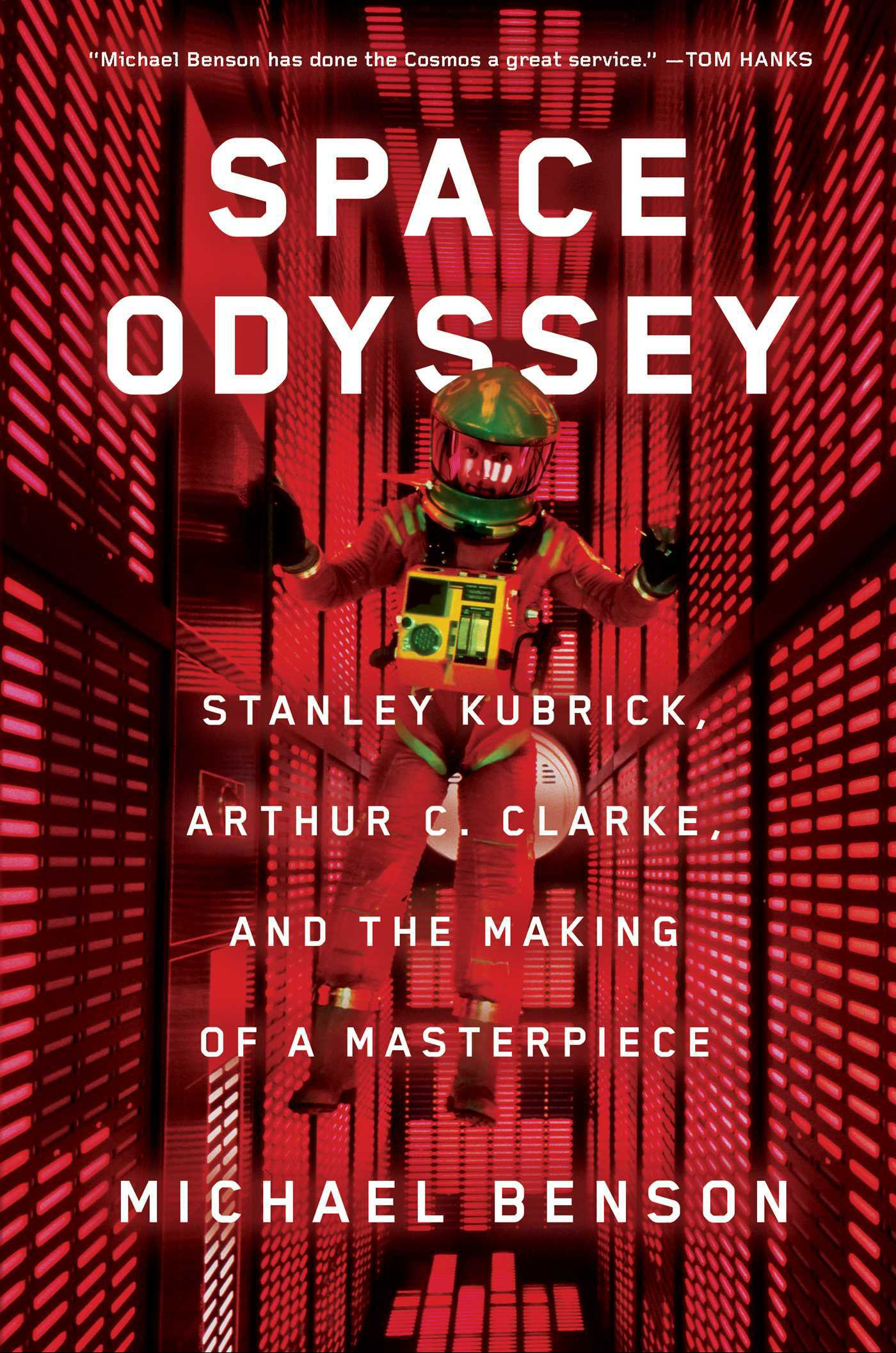

2001 was now the best movie I’d ever seen by leaps and bounds, a position challenged only once, about four years later, by a 16mm print of CITIZEN KANE in a grad-school film history class. Nothing else since has even come close. I’ve probably seen the flick twenty times by now and I feel like I know it pretty well. I’ve read every snippet I could find about it. So imagine my surprise when a new book for 2001’s fiftieth anniversary managed to take me to school dozens of times with endlessly fascinating arcane details. Michael Benson’s SPACE ODYSSEY is the only book on the subject you’ll ever need.

Stanley Kubrick was on my radar for making the hilarious and transgressive DR. STRANGELOVE, but that’s all I knew about him. Only that this big-time director had teamed with science fiction titan Arthur C. Clarke to come up with a serious outer-space movie. My card-carrying, propeller-beanie-wearing sf fan’s heart fluttered. Plus, the normally secretive Kubrick had really clamped the lid shut on this production (Mr. Benson explains why). So we knew nothing, and we were dying. Of course we’d drive 200 miles, watch a movie, and drive right back!

The “road show” was how big extravaganzas were introduced back then: BEN-HUR, DR. ZHIVAGO, CLEOPATRA, THE TEN COMMANDMENTS, HOW THE WEST WAS WON, etc. The initial engagement was restricted to larger cities. Reserved seats. An intermission. Printed programs. But this one had the added attraction of Cinerama, large-format film projected onto a giant curved screen to suggest peripheral vision, with audio speakers everywhere for the first surround sound I’d ever heard. We bought our tickets by mail, positioning ourselves in the Cinerama sweet spot, a third back in the dead middle. As we were filing in, this strange spacey “music” (which I now know to be György Ligeti’s “Atmospheres”) softly caressed the auditorium because the film was already rolling. It was perfect. You can hear the Ligeti “overture,” just as we did, on the 2007 Warner Bros. Blu-Ray edition, which attempts to replicate the 1968 roadshow experience. Christopher Nolan — an excellent choice — is working on a 4K release for October of this anniversary year, but if you don’t have the gear, then the 2007 Blu-Ray is still your must-own version. We may not have Cinerama to play with any more, but after years of watching 2001 on tiny cathode-ray tubes, we’re finally arriving at large-screen hi-def home-theater tech that better deserves this film.

What we saw and heard was another kind of science fiction, another kind of art itself. 2001 is largely a nonverbal experience. Dialogue is heard for barely a fourth of its 142 minutes; the first spoken words (“Here you are, sir”) occur a full 22 minutes in. The pace is languid (more impatient viewers consider that a bug, but I think it’s a feature) and deliberate. The story begins four million years ago and ends — well, that was the biggest topic on the way back home. And before your eyes is the most authentic-looking (eventually Oscar-winning) simulation of outer space ever put on film. I’ve never seen more convincing space effects in the ensuing half century, not with computerized motion control, not with CGI.

Dan Richter as “Moonwatcher.”

By now 2001 feels so — inevitable, that it’s remarkable to learn from Mr. Benson how many decisions were actually made on the fly. Stanley Kubrick was an intensely driven, naturally curious polymath on whom the term “genius” was not squandered, as we frequently tend to do. His personal aim went beyond excellence and approached perfection, and he demanded the same fierce focus from his colleagues. The book is full of examples of artists and craftsmen striving to please Stanley, when what he really wanted was for them to surpass their presumed capabilities: he was a tyrant who still engendered devotion and even love. Many of 2001’s physical requirements were “impossible” given the technology of the day, so the production had to inquire, improvise and even invent. The many innovations developed for the film could fill a book, and now they have.

Mr. Benson is the ideal guide. Not only has he done voluminous research, but he is also a visual artist and filmmaker as well as a writer — and though he treats 2001 with a true fan’s respect, he’s not above having a little fun with his subject. As Kubrick and Clarke struggled for an ending, in one screenplay draft an “unbelievably graceful and beautiful humanoid” was supposed to approach the lead character and lead him into “infinite darkness.” As Mr. Benson writes, “how to achieve such grace and beauty had been left indeterminate. In any case, it wasn’t just inadequate, it flirted with risibility. Kubrick didn’t do risible.” He compares the creation of the trippy 17-minute “Star Gate” sequence to jazz improvisation among 2001’s “image instrumentalists”: “Like John Coltrane leaning into the mike after Miles Davis was done, [visual effects supervisor Douglas] Trumbull figured he’d take his turn.”

SPACE ODYSSEY is also a bagful of surprises. For example, I already knew that Canadian actor Douglas Rain provided the voice for 2001’s HAL 9000 supercomputer in two days without seeing a foot of film or any lines besides his own. But I didn’t know that Rain was the second actor to play HAL. The first was Martin Balsam, but later the director decided that Balsam had added too much personality and instead chose to go deadpan. Another thing I didn’t realize was that the “breathing” sounds heard when main characters are in their spacesuits were “acted” by the director personally, who recorded about a half-hour’s worth of “respiratory soundscape” wearing one of 2001’s prop helmets. Thus, as Mr. Benson notes in a lovely bit of writing, “as an example of his own handiwork, Stanley Kubrick’s film 2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY bears evidence of his own life within it, a small segment of his human soundtrack.”

The book is stuffed with little mini-dramas. There is mime Dan Richter’s laborious research and choreography for the “Dawn of Man” sequence (he plays “Moonwatcher,” the lead ape). The physical struggle to get daredevil flyover footage for inverted, solarized Star Gate shots, or Namibian landscapes for front-projection plates. The tug of war over Clarke’s companion novel, which Kubrick kept delaying along with the general production. Kubrick’s campaign to keep MGM at bay as the production slid egregiously over budget and behind schedule. The fate of a narration to help “explain,” which Clarke slaved over for years. The agony of would-be composers facing Kubrick’s determination to use the Strauss and Ligeti “temp tracks” he’d already dropped in (in hindsight they’re as right as can be, but the first time Kubrick saw the space-station footage against “The Blue Danube,” he asked, “Do you think it would be an act of genius or the height of folly to have that?”).

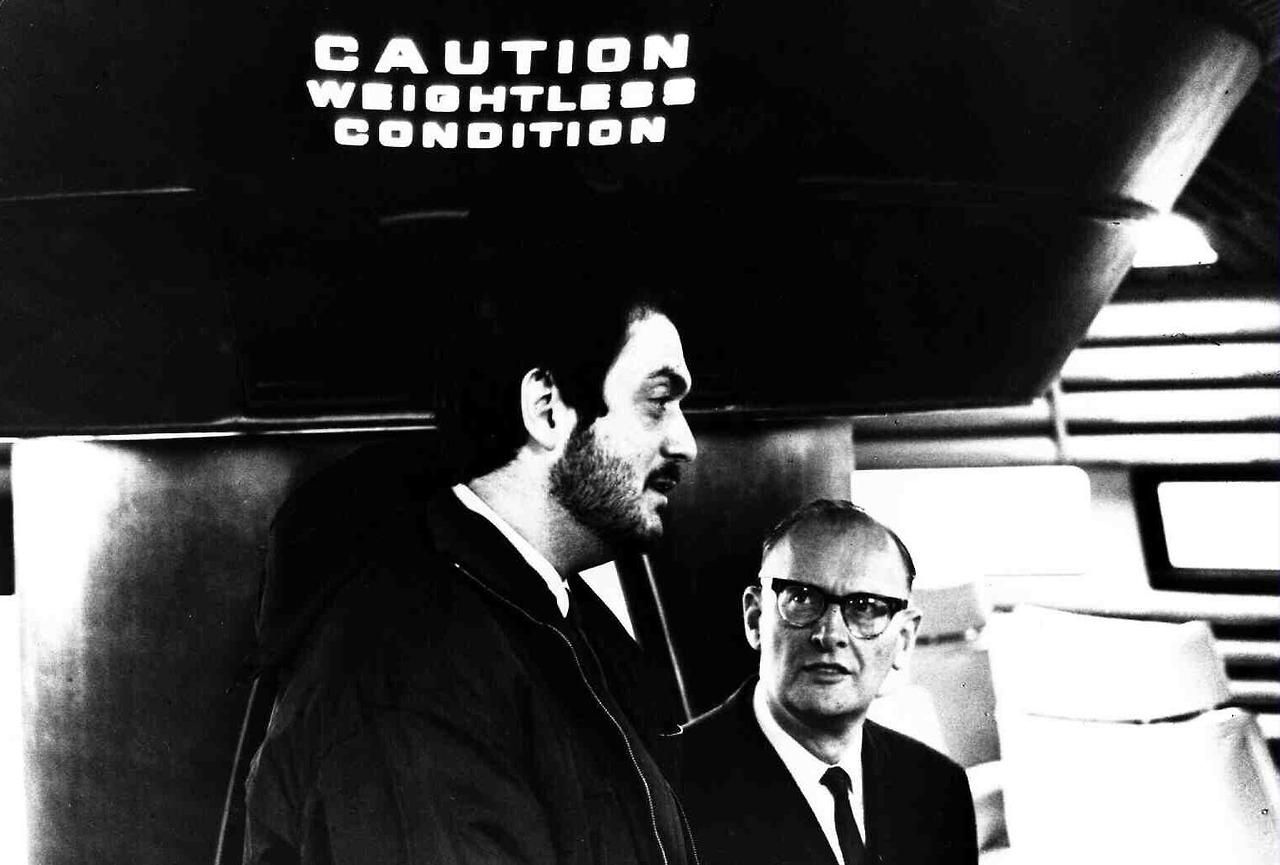

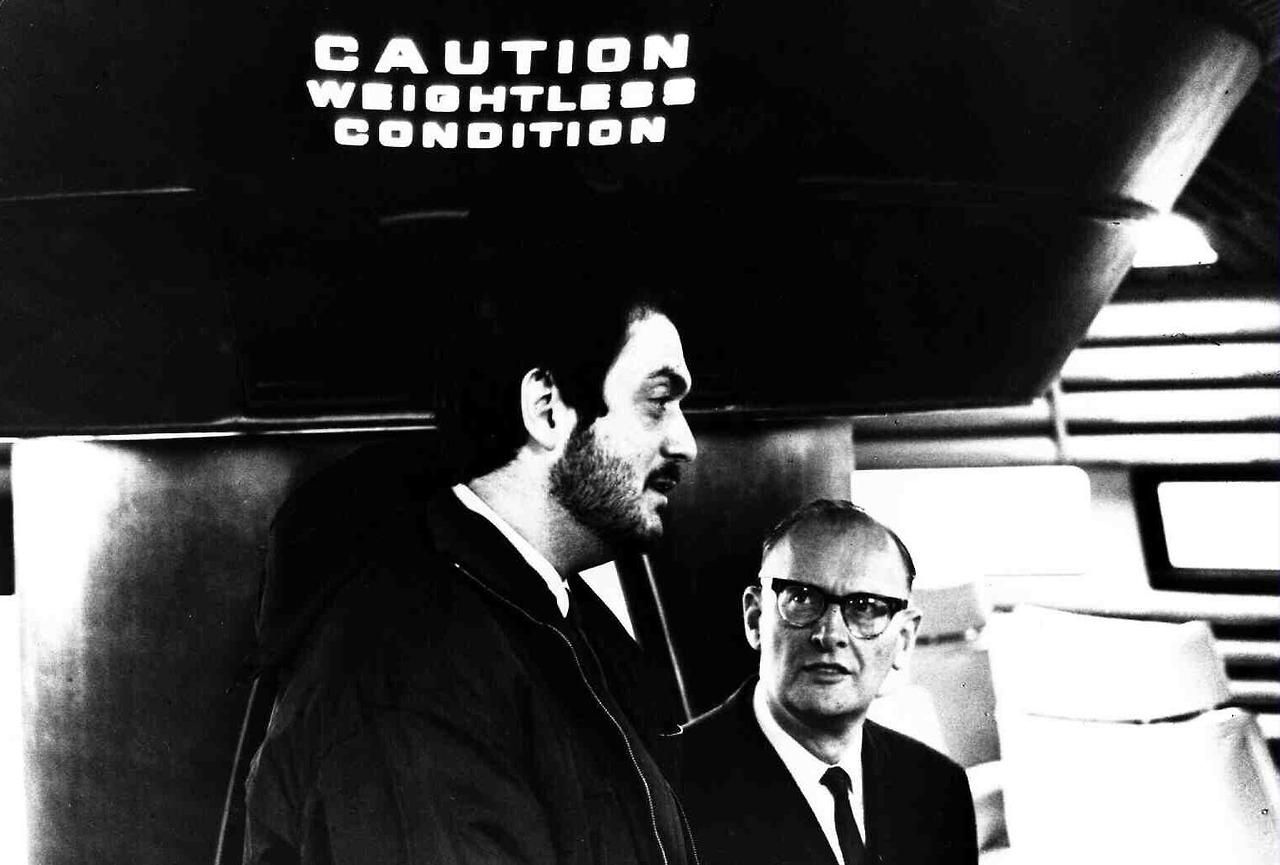

Kubrick (l.) and Clarke on set.

A bit of unexpected lagniappe came my way whenever the book located the production’s New York phases. (2001 was Kubrick’s last project not fully restricted to England.) The first film exposed for 2001 was high-speed footage of drops of colored paint in a tank of black ink and thinner, used in the finale. Kubrick himself operated the camera in an abandoned brassiere factory on upper Broadway, just a few blocks from where I lived when I first moved here 23 years later. Kubrick’s Lexington Avenue penthouse apartment, where lots of 2001 was hatched, was just three streets down from where I’m sitting right now. And years later, following a disastrous first screening, Kubrick trimmed the finished film in the basement of the MGM building on Sixth Avenue: I worked there when I was with the Hearst Book Group.

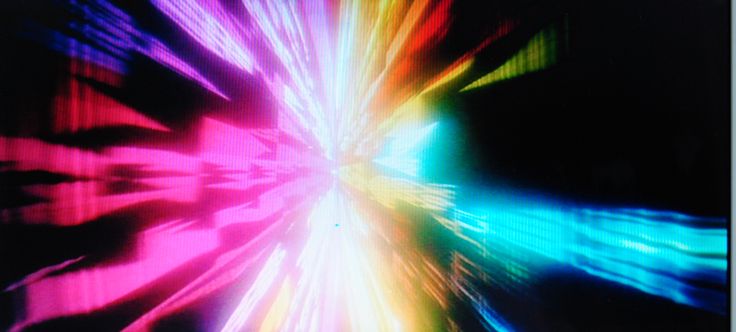

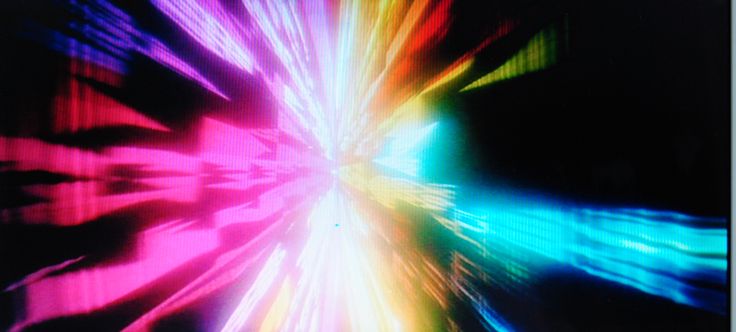

Kubrick is the boss, but he’s not always the hero. It took VFX master Doug Trumbull — who learned his craft on this show — decades to forgive the director for including an end-credits card reading “Special Photographic Effects Designed and Directed by Stanley Kubrick.” There was actually a plausible reason for this: Academy rules prohibited more than three people from being considered for a VFX Oscar (same deal with Best Picture producers today), but 2001 had four credited special effects supervisors. So the solo credit probably kept 2001 under consideration, but Kubrick might have petitioned the Academy to bend the rules for such a quantum-leap production. Kubrick personally realized the oil-and-paint “galaxy” effects back on Upper Broadway, and he knew more about teasing results from photographic equipment than most DPs. But the space effects were definitely a collaborative effort, as this book richly illustrates, and he didn’t nail the “Purple Hearts” solarization technique discovered by Bryan Loftus, or Trumbull’s own “slit-scan” machine, both of which provided indelible images for the Star Gate sequence. What Kubrick did get was the only Academy Award he ever won. My impression is that what really stuck in Trumbull’s craw was the word “Designed.”

Doug Trumbull’s “slit-scan” effect.

The most important thing Mr. Benson does for me personally is to finally scratch an itch that has persisted for fifty years. As all true fans know, 2001 was reviled upon its premiere but gradually caught on later. Well, no. That’s not what happened at all. The version which premiered in Washington, D.C. on April 2, 1968 and in New York the next day — crucially, the one that was shown to the nation’s film critics — was 161 minutes long. The dismal reaction (although he wisely kept his mouth shut, even Clarke hated it) traumatized Kubrick and forced him to call for intensive surgery in MGM’s basement OR at good old 1350 Avenue of the Americas, where he delicately excised nineteen minutes. For half a century, I have been dying to see that nineteen minutes. If 2001 is this good, wouldn’t that make it nineteen minutes better?

Mr. Benson has disabused me of that desire.

We know and love the sequence in which Gary Lockwood jogs and shadowboxes in a 360-degree antigravitational loop — a mind-blowing illusion performed on what was then the largest kinetic set ever constructed. Some people think the scene goes on too long. Well, how about another 360-degree sequence featuring co-star Keir Dullea? The premiere audience saw it. Also, Dullea meticulously prepares for an EVA at the computer’s suggestion. Again, even today some viewers (not me) find the sequence fat. How about doing it yet again with the other astronaut? The filmcrits saw that too. 2001 is so hypnotic that a rapt audience member could even acquiesce to all this. But most others, nuh-uh. Kubrick didn’t know this because he’d never tested the super-secret film with real warm bodies: nobody had seen the virgin reactions of completely objective viewers. Whether MGM forced the cuts or not is unclear, but even Kubrick had to concede they were necessary.

At a trimmer 142 minutes, not only did 2001 immediately roar for MGM at the box office — it was 1968’s highest-grossing film, the only time Kubrick ever achieved #1 — but critics also began changing their minds upon subsequent viewings. Jeez, this is nowhere near as turgid as I remember! The funniest opinion morph, reprinted in Jerome Agel’s 1970 pop-arty THE MAKING OF KUBRICK’S 2001, was Time magazine’s weekly 25-word capsule movie review section from preem to dominance: it was as if different people had written each of eight or ten entries. Ash heap to masterpiece.

Let’s leave it at masterpiece, for that’s where 2001 sits in my home. Therefore I’m not capable of judging this book objectively. Would it be as compelling to someone who has never seen 2001? Dunno. But only a couple of sentences on physical engineering were beyond me (kudos to the author, who keeps the rest of it earthbound), and I would imagine the fraught journey toward a lasting work of art could interest a seeker from any medium. If you haven’t yet had the pleasure, my strong advice would be to see the movie before you dig any deeper. Get as close to our college-boy innocence as you can. Slow down. Lights off. Breathe. Exhale. Quiet. Still. Now hit play and dig some Ligeti.

10/28/18: Now I’ve seen the 4K transfer. Magnificent. It makes some of the tiny traveling mattes (like the little teeny views of red-lit cockpits) look worse, but almost all the space shots (like the one below) look amazing. Every once in a while you have to pinch yourself and say, this mutha is fifty years old!

11/13/18: Douglas Rain, the voice of HAL, has passed away.

The best damn space effects in film history.

Posted by Tom Dupree

Posted by Tom Dupree