Rush Limbaugh built an empire on unfairness, and boy, did it catch on.

Most Americans are too young (*sigh*) to remember when radio and tv broadcasts were subject to the “Fairness Doctrine,” established in 1949 by the Federal Communications Commission. Along with an “Equal Time Rule” which applied to political candidates, the regulation mandated the presentation of opposing points of view on controversial issues or political endorsements. What right did the FCC have to stick its nose into local broadcasters’ business? Because the airwaves are owned by the public and only temporarily licensed to for-profit companies.

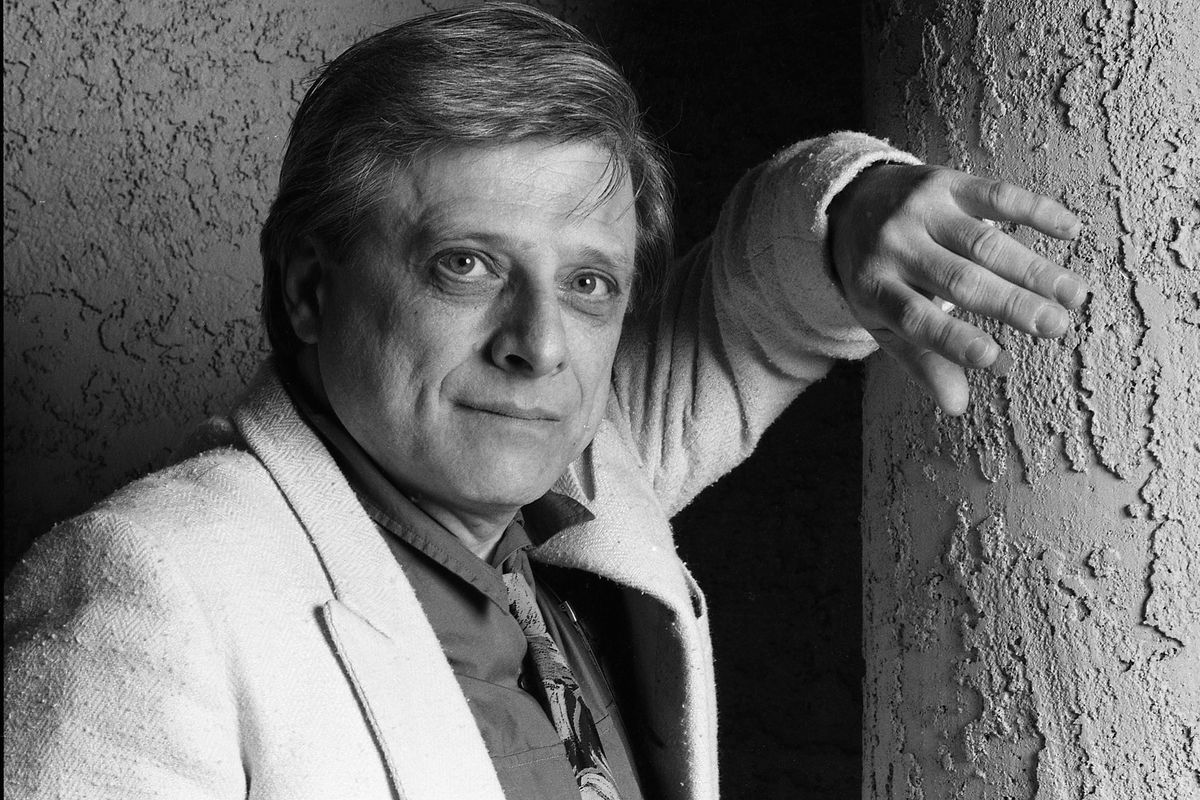

One of the signature features of 60 MINUTES when it debuted in 1968 was a segment called “Point/Counterpoint,” in which liberal Nicholas von Hoffman and conservative James J. Kilpatrick debated a particular topic. As Shana Alexander took over for von Hoffman in 1975, making the segment a de facto battle of the sexes, SATURDAY NIGHT LIVE was just going on the air. In SNL’s early years Jane Curtin and Dan Aykroyd had a ball satirizing these debates: “Jane, you ignorant slut!” That line was funny because the real thing was all about ideas, not personalities, and 60 MINUTES’ back-and-forths were conducted with the utmost propriety. The fact that such a respectful atmosphere now feels innocent, even quaint, can be traced directly back to El Rushbo.

There was talk radio during those days, it was just very different. When I lived in Georgia in the early Seventies, on long car trips I loved tuning in to WRNG (“Ring Radio”), an all-talk station in Atlanta. Each jock had a four-hour show and spent it all on telephone call-ins. The host could steer callers toward a topic, but the real stars were the civilians on the line. You could hear crazy tinfoil-hat conspiracy theorists, but a later caller would usually inject a dose of reality. Even then, though, I noticed that the ranters were more entertaining. One of the WRNG personalities was a guy named Neal Boortz. He was still doing his thing as late as 2013, but something had long since changed. For WRNG he was a forensic referee, but over time he morphed into fire-breathing right-wing bombast. This is how it happened:

In 1987 the Reagan administration repealed the Fairness Doctrine, claiming that there were so many media voices in the marketplace that it was no longer needed. Now you could say whatever you wanted without opposition or reproach. The following year a radio syndicator hired a glib 37-year-old Sacramento jock at exactly the right time, and offered his conservative-oriented show for next to nothing as long as you agreed to run three or four minutes of “national” ads. The rest of the commercial time was yours. THE RUSH LIMBAUGH SHOW was eventually carried on more than 600 stations, the reach ever larger and larger as the show moved around to bigger stations at contract renewal time.

By the late Eighties the radio business had been fighting to stay standing in the midst of several cultural hurricanes. For decades a leading and lucrative format had been “Top Forty,” or repeated playing of popular rock and pop singles. But since the late Sixties music fans had been enticed by the clarity and range of album-oriented FM stations. Then in 1981 MTV went on the air and supplanted Top Forty radio as the best way to “break” new acts and records. The business was anemic when Rush came along and changed everything — and AM was just dandy for talk, which doesn’t require a Bang & Olufsen rig to enjoy. Most broadcasters will tell you that Rush Limbaugh is the guy who personally saved the AM dial by paving the way for so many others.

While Rush was emerging to lead the conservative ecosphere, I was in New York working in the book business. One day in 1992, when I was at Bantam, a competitor of ours, Pocket Books, released THE WAY THINGS OUGHT TO BE and it shot to the top of the bestseller list. I had never heard of Rush Limbaugh, but a ton of book buyers sure had. I asked our publicity czar, Stuart Applebaum, if he could explain the new publishing pheenom. “Conservatives don’t have anything to read,” he said. (They do now, even have their own imprints; one of them, Regnery, recently picked up Sen. Josh Hawley’s discarded book after he basically fist-bumped the murderous Jan. 6 mob at the Capitol, triggering a Simon & Schuster morals clause.)

I had to know, so I got a pal to send me a copy and took it home. Although I had still never heard the sound of Limbaugh’s voice — the thing that made him famous — I think I managed to get a load of his public persona all the same. He was an extreme reactionary, brash but so over the top that he was funny too. He clearly saw himself as an entertainer, not a journalist. Some of his provocations were nothing more than a way to get under the skin of the other side, to “own the libs.” Heck, El Rushbo invented owning the libs. But he did it with unrepentant flair. For example, his network was modestly called “Excellence In Broadcasting.”

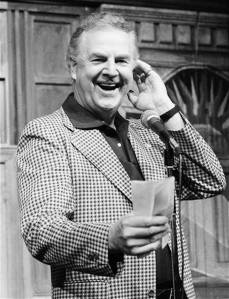

When I heard him speak for the first time, we were in the same room. The following year, I happened to be in the David Letterman studio audience for Rush’s first guest spot, promoting his second book SEE, I TOLD YOU SO on Dave’s old NBC late-late show. By now people outside the Limbaugh fan base were vaguely aware of him, so he knew he was in the lion’s den. He demonstrated comfort and good cheer, got that faux-boastful personality stated, and ably dealt with a rather hostile crowd (“Let the wrestling begin,” said Dave at one point) while getting his jabs in at the Clintons to groans but smiling all the time. Looking back, I think Rush always resonated not just for what he said, but the way he said it.

Yes, the media probably did have a liberal bias — truth itself has a liberal bias — so to many conservatives it was a novelty hearing a point of view that actually reflected their own. Rush was speaking for them so accurately that his fans took to calling themselves “dittoheads.” Damn right, Rush: ditto! But anybody can spout reactionary wisdom. What set Limbaugh apart were his terrific performative chops — he could vamp like a jazzman — and a carefree attitude that deflected so many incoming bad vibes like the ones in that NBC studio.

That verbal Fred Astaire touch is why Rush is irreplaceable. Today’s conservative stars, especially on the Fox News Channel — whose high concept on its launch in 1996 was basically “Rush Limbaugh On TV,” and whose slogan “Fair And Balanced” owned the libs at gut level — are stern and humorless. Sean Hannity, Tucker Carlson and all the Fox blondes are simply selling outrage, not right-winger fun, and that’s hard to sustain. Remember when Dubya’s color-coded Homeland Security Advisory System remained at “elevated” risk for terrorism every day for months? You can’t keep it up. For longevity you need a song and dance man, a “rodeo clown,” as Glenn Beck memorably described himself. Which brings us to that orange guy, the one with the bizarre combover who cheats at golf. That doofus was nothing but a Rush Limbaugh imitation, and a poor one at that.

Talk about dittoheads. They even amazed the game show host turned candidate: he could shoot someone on Fifth Avenue and not lose any voters. He may or may not have been surprised when a violent mob did exactly what he told them to do, but there’s no denying he was fascinated. His whole reason for being was owning the libs. He was cruder and dumber than Rush, but even the old broadcaster had to be impressed by the idea of receiving the Presidential Medal of Freedom during the State of the Union address. Hi, libs!

The portly loser of the 2020 election took his cues and even some of his cadences from Rush, who never missed a chance to use Barack Obama’s middle name, now as much a part of conservative nomenclature as is “Democrat,” as in “the Democrat majority in Congress,” and was all in on “birtherism.” At least Rush was most often punching up, a concept that eluded Mr. Obama’s successor (all bullies are frightened when they must face real power). But not always. The fast-food fan’s shameful pantomime of a physically lesser-abled reporter mirrored Limbaugh’s odious burlesque of Michael J. Fox’s Parkinson’s condition, one of the lowest moments of his career. The guy with the crotch-length neckties has a propensity for grade-school derisive nicknames, his bathetic attempt to emulate Rush’s genius for coinage, as with his word “feminazi,” which is both malevolent and funny at the same time. Of course, Limbaugh once held up a photo of thirteen-year-old Chelsea Clinton and called her the “White House dog” on the air, so he has certainly wallowed in similar disgusting muck.

Most of all, Rush Limbaugh spent three decades stirring the cauldron of conspiracy that now composes the entire Republican Party. Reason is for saps. You can believe yourself the victim of a vast government conspiracy while at the same time believing the bureaucracy to be incapable of the simplest actions. You can hate “blue-state bailouts” when your own red states depend on them to subsidize your existence. You can scream for law and order while you are commandeering a state or federal capitol building. You can call for deportation of undocumented immigrants while taking advantage of their willingness to do highly physical or unpleasant jobs. The way things ought to be, Rush explained, and then see, I told you so.

When the word spread that Rush had passed away yesterday morning from complications of lung cancer, one Facebook poster quoted Bette Davis: “You should never say bad things about the dead, you should only say good. Joan Crawford is dead. Good.” While I wouldn’t go that far, Rush Limbaugh was responsible for encouraging the bitter tribalism that keeps Americans from solving common problems. But he couldn’t have done it without the complicity of his audience. I hope enough dittoheads will be forced to use their own brains now and perhaps rediscover comity in the bargain.

Posted by Tom Dupree

Posted by Tom Dupree

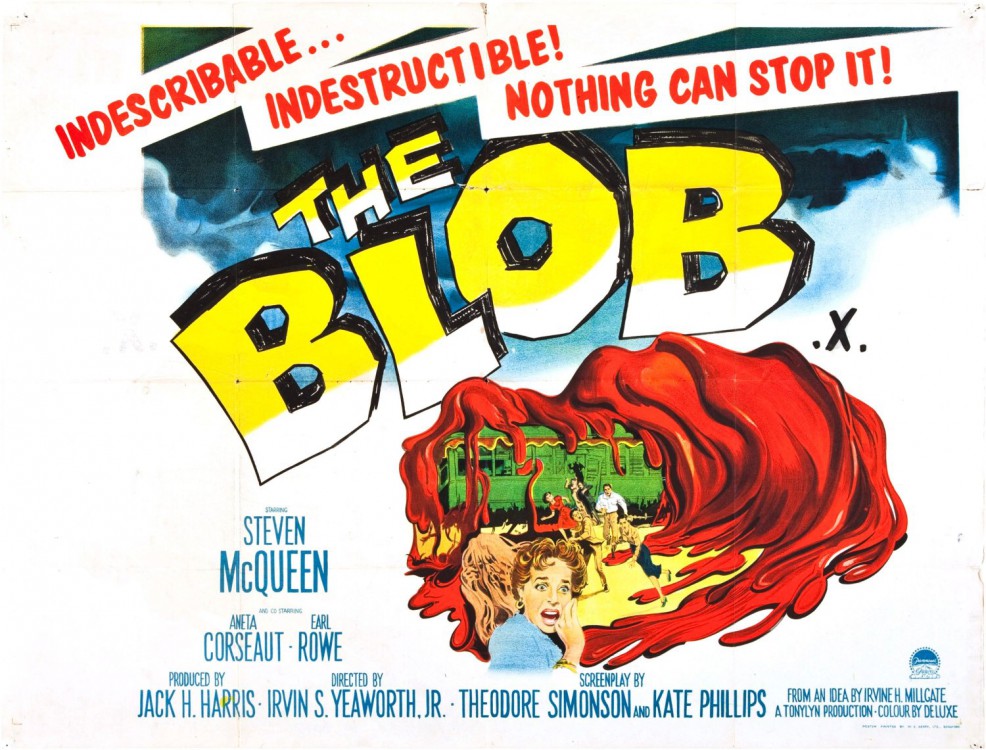

It was the age of exploitation in the movie business as the industry frantically swatted away against the incursion of television on its customers’ leisure time: movies needed to be — or at least seem to be — bigger, bolder, better. Plus, by the late Fifties the recently christened “teenager” had developed into its own lucrative category for marketers. As another contemporary showman put it, these kids loved cars, girls and ghouls. So movie after movie gave it to them. And towering over them all was a big ball of malevolent jelly, the frickin Blob.

It was the age of exploitation in the movie business as the industry frantically swatted away against the incursion of television on its customers’ leisure time: movies needed to be — or at least seem to be — bigger, bolder, better. Plus, by the late Fifties the recently christened “teenager” had developed into its own lucrative category for marketers. As another contemporary showman put it, these kids loved cars, girls and ghouls. So movie after movie gave it to them. And towering over them all was a big ball of malevolent jelly, the frickin Blob.

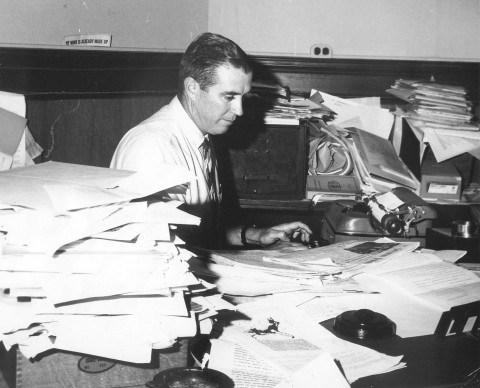

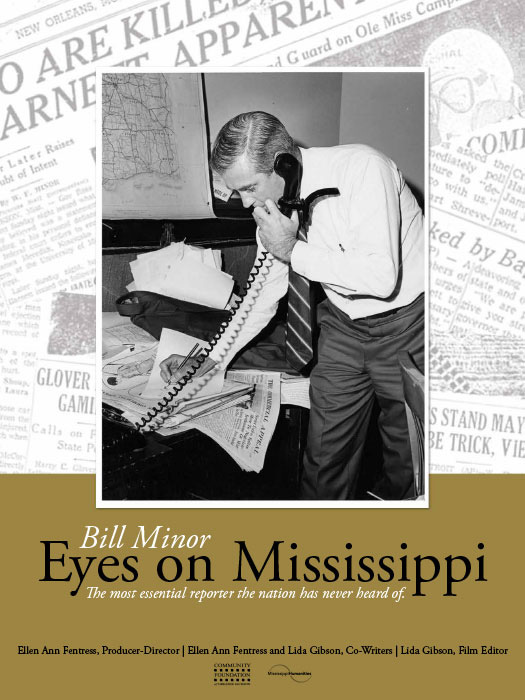

I wrote this the week Eudora Welty passed away and just found it again after all these years. It’s for her friends and admirers.

I wrote this the week Eudora Welty passed away and just found it again after all these years. It’s for her friends and admirers.