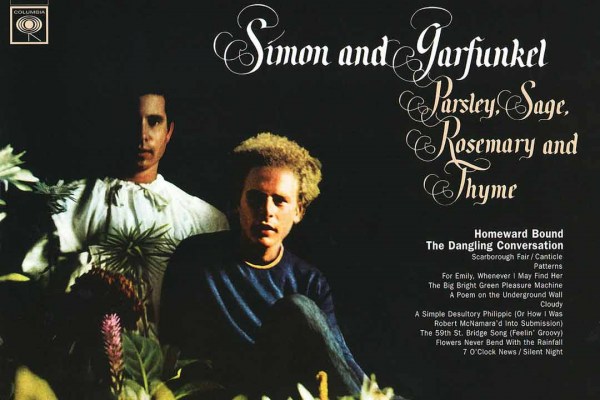

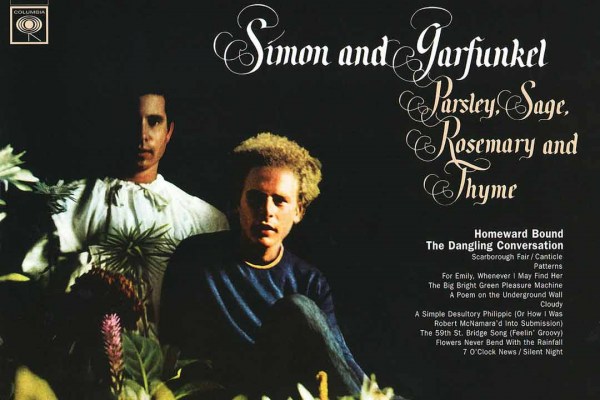

I like to listen to music while I cook, but as with my diet I want variety. So I have this long playlist of music I love, and I just ask Alexa to shuffle it as I pull out the cutting board. I never know what’s coming next. The other night, what popped up was “Scarborough Fair/Canticle,” the opening track of Simon and Garfunkel’s album PARSLEY, SAGE, ROSEMARY AND THYME. Wow, that sounds pretty good, I thought. Wonder how the rest of the album holds up? So later that night I revisited the whole thing, in order, after half a century.

Yes, PARSLEY, SAGE, ROSEMARY AND THYME turned fifty last October. When it was new I was just starting my senior year in high school. Lots of water has flowed under the bridge since then and nearly everything has changed, most definitely including the music business. Its mid-Sixties conventions are almost unrecognizable today.

In 1966, in the artistic sense, we were all still trying to figure out what a “record album” was. The term originated to describe hardbound packages of single-track 78rpm disks, bound in sleeves with big holes in the middle so you could read the labels, which you flipped through just like a photo album. Those clunky beauties are long gone but the name has stuck. A single-artist collection is still an “album,” whether you buy it on a shiny silver disk or stream it down those Internets.

For pop acts, the arrival of the long-playing 33 1/3rpm single-disk “album” was largely a non-event. Throughout the Fifties, Lps — assuming you had the gear to play them — were mostly for Broadway cast recordings, which regularly topped the Billboard charts, or longer jazz or classical pieces. Pop songs, including the emerging rock & roll sound, were distributed on smaller 45rpm “singles.” That’s what filled up juke boxes, that’s what the Top 40 DJs spun on the air, that’s what teenagers stormed the record stores to buy.

The altruistic saints of the record companies, always looking for ways to devote their own modest profits toward the greater good, made some calculations as the Lp took hold. A single retailed for the better part of a buck for two songs, the chart hit and an unknown “B-side.” (Sometimes they both became hits, as with Ritchie Valens’s “Donna”/”La Bamba.” Too bad, thought the benevolent angels: that leaves some potential philanthropic donations on the table. Should have been two releases.) Slap a bunch of singles on an Lp, though, and you could charge the kids three, four times as much and repurpose the studio time you’ve already written off — for charity! Add yet another buck for stereo! (“360 Sound” at Columbia.)

So, while more customers got used to Lps, almost all the big pop album releases were by and large collections of previously issued singles, except for the white-collar folk revival (“The Great Folk Scare,” as Dave Van Ronk called it) and sui generis artists such as Bob Dylan. Even Dylan and other oddballs still observed conventional graphic design, listing every song title on the front cover to make the package look like more of a bargain. Dylan’s first four album covers featured song lists, though he’d probably never been heard on a Top 40 radio station and most customers had no clue until they spun the platter.

By the mid-Sixties, however, forward-thinking artists, even popular ones, were starting to kick in their stalls and strive to turn their albums into unique events. PARSLEY, SAGE is a relic from the midpoint of that transition. It’s a collection of newish songs (funny, they don’t look newish!), but three of them had already been released: “Homeward Bound” and “The Dangling Conversation” were legit chart hits, and “Flowers Never Bend With The Rainfall” was the B-side of the huge “I Am A Rock” single (I bought that one, in fact, just to get a new S&G song). There’s a song-title list on the cover, the two hits in big bold face, but the rest of the record besides “Flowers” was a cipher until you played it for the first time.

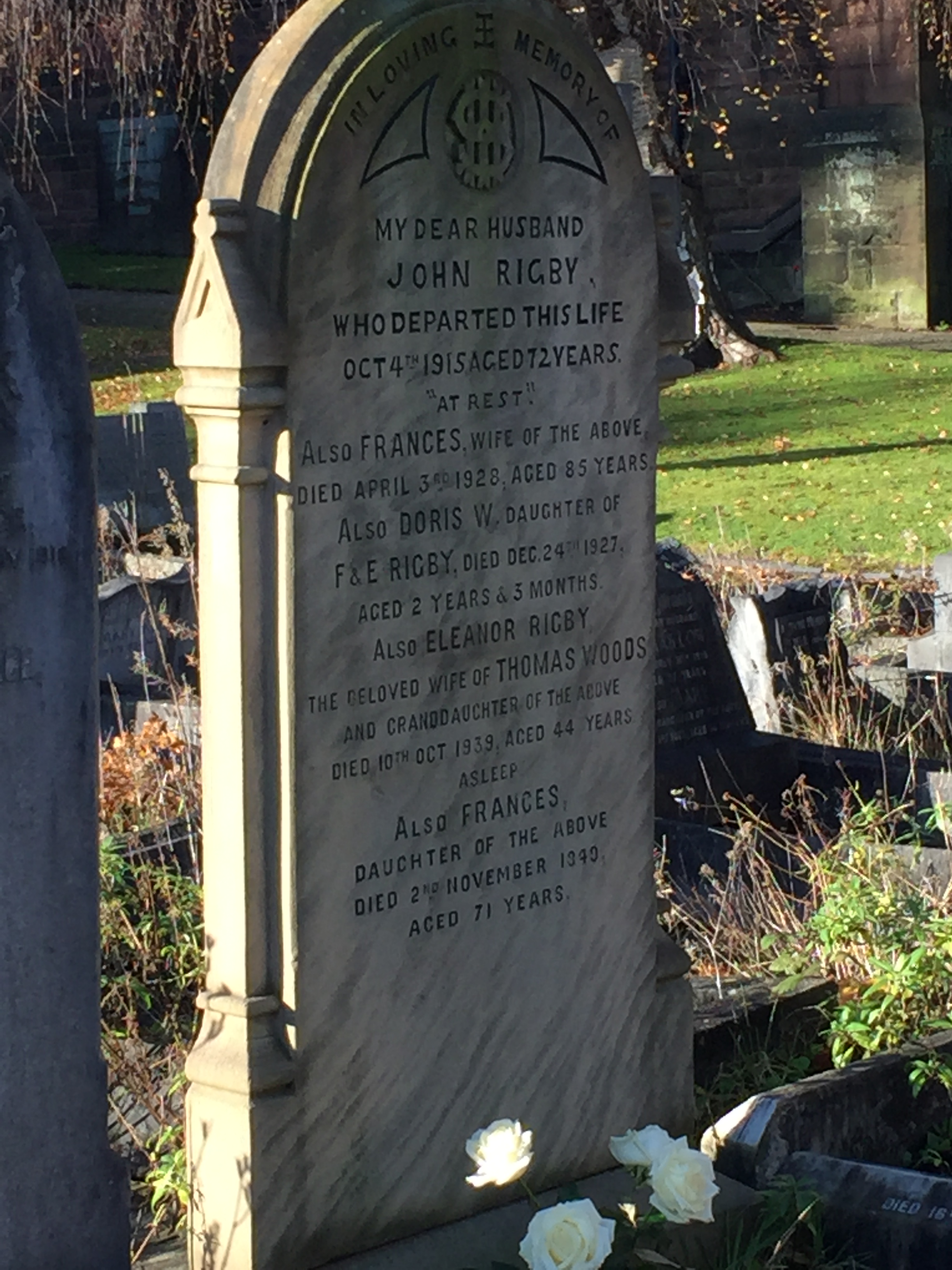

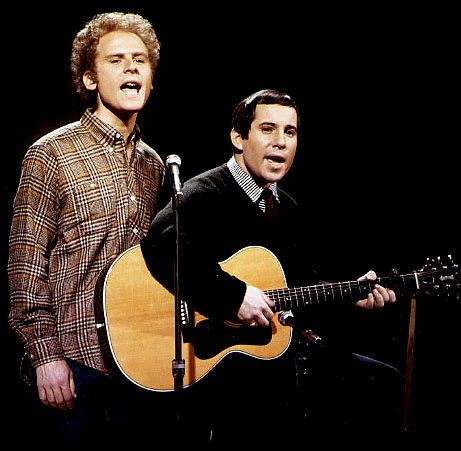

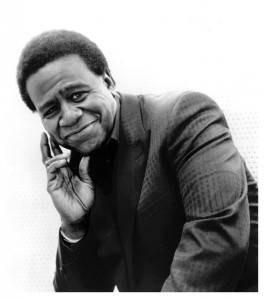

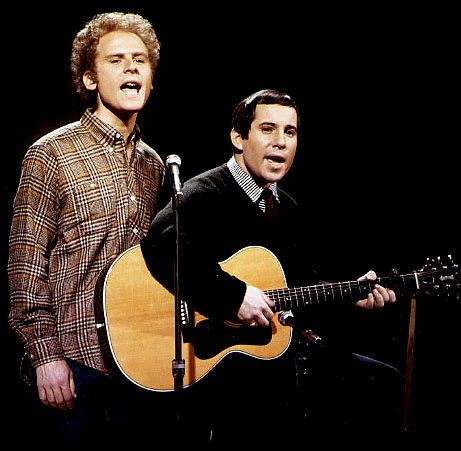

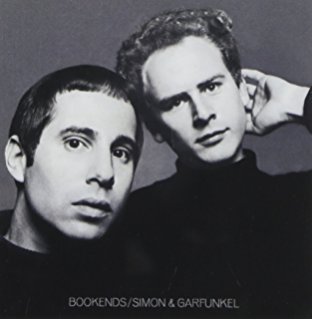

Artie and Paul, about the time they recorded PARSLEY, SAGE.

PARSLEY, SAGE was also halfway conventional creatively. Its twelve tracks clock in at a total of just under half an hour; the longest one, “Scarborough Fair/Canticle,” is only 3:10. But this material was more densely packed than anything I’d ever heard. It was partly a reaction to S&G’s rushed-out previous album SOUNDS OF SILENCE. They had already split up when, after the fact, producer Tom Wilson overdubbed rock instrumentation onto the acoustic recording of “The Sound of Silence” from their non-selling folkie Lp WEDNESDAY MORNING 3 AM. That second-hand backbeat irked Paul Simon when he heard it, and furthermore the tempo wavered enough on the original that the dubbed electric cats had to audibly slow down once to let the vocals catch up. But the new mix made Simon and Art Garfunkel huge stars when it became a smash, causing them to reunite for that quickie follow-up. Now they were big shots, and now they were going to take their time. They spent a then-unheard-of three months recording PARSLEY, SAGE, establishing a lasting reputation as studio perfectionists, sort of the Steely Dan of the Sixties. I could hear a quantum leap in ambition the first time I played the record in fall 1966. I thought it was one of the best things ever. No lie. It was the same feeling I got when I first saw CITIZEN KANE and 2001.

If most albums at the time were hit-record compilations, they still worked because the artists had a signature sound that sustained itself throughout. While it was true that Simon & Garfunkel harmonized so beautifully that you often couldn’t tell which one was up high — they sang intervals like their idols the Everly Brothers, but without a hint of country twang; they may have sounded like altar boys but were really two Jewish kids from Queens — each track on PARSLEY, SAGE inhabited its own individual sonic environment. It felt less like a greatest-hits record and more like a collection of great short stories. Even the magnificent BLONDE ON BLONDE, which beat PARSLEY, SAGE to market by six months or so, didn’t exhibit such variety and exactitude. I was blown away.

How did I react five decades later? Spoiler Alert: ambivalently. The newness has worn off. Some PARSLEY, SAGE tracks are still hands-down classics, others have lost a bit of luster. But that short half hour is still crammed with so much creative thought that it cannot be denied.

“Scarborough Fair/Canticle” meets one’s expectations with a soft opening guitar figure. I’ve always admired Paul Simon’s acoustic guitar playing and you can tell it a mile away. He’ll pluck way down on the lower strings and almost slap them for emphasis to get a violent percussive attack: it’s the first sound on the next song. (The axe work on the Everlys’ “Wake Up Little Susie” clearly impressed the young Master Simon.) This jagged rhythmic effect is a cousin to the wonderful pick-heavy style that James Taylor brought along later. The boys begin their new album with an innocent medieval air, seasoned with some harpsichord fillips that favor Paul’s puffy shirt on the cover photo. But then something intrudes, “signaled by the electric bass,” as Ralph J. Gleason writes in his liner notes. It’s a countermelody, a darker countersong that fills the gaps on the road to Scarborough with the same sweet voicing, but starts to drip menace. Something about polishing a gun, war bellows blazing, scarlet battalions, generals ordering death, it becomes a real nightmare. You can concentrate on either thread — sort of choose to sip wine or chew some food — or just let the total sound wash over you as when a balance of wine and food produces a third taste. I don’t know which member found the harmony (I hope it was Artie) but this is our first iteration of what would become a signature S&G effect, the high note from way off in the rural areas of the chord. You can hear it clearly on the final “THYYYYME…” Even in mono — I didn’t have the money or gear for stereo at the time — there’s an expanse to the track, as if it’s being performed in a large room or from a fair distance. Surprise upon surprise. As I said, this was the one that recently made me interested in hearing the entire album again. I think it still works, though by now we who have followed all these years are already expecting the “Canticle” descant (most amateur performers omit this part).

It sounds more like a normal recording studio on “Patterns,” a minor-key rumination that puzzled me even in high school, from whence much overreaching poetry springeth forth. Also, somebody brought some bongos to the session. Unless meaning is actually being obscured, I’m not a grammar nazi (screw that missing Oxford comma in the album title!) but I couldn’t hear the song back in the day without getting stuck on these lines: “Impaled on my wall / My eyes can dimly see / The pattern of my life / And the puzzle that is me.” In other words, somebody ripped out Paul’s eyeballs and nailed them to a wall, yet in the early evening gloom they can still perceive images. Seriously, I get that he’s trying to refer to the pattern, but why impale it on his wall? For that matter, not to second-guess the bard or anything, but what’s so awful about patterns in the first place? I’ll bet even Simon considers these lyrics to be juvenilia. The solution is to chillax, put down your microscope, and listen to, as Donald Fagen once put it, “the sound of the phonemes.” Just enjoy the groove as I learned to. But still: impaled eyes?!

Simon & Garfunkel had been the avatars of alienation, full of angst and woe, so it was a bit of a novelty to hear the jaunty “Cloudy.” Here again, the chorus is pure existential sighing: the clouds are gray, they’re lonely, they hang down on the singer, they don’t know where they’re going. But the verses brighten into pure joy — though the boys are about to go to 11 with the endorphins in a few minutes — maybe because they were co-written by (but not credited to) the Seekers’ Bruce Woodley, with whom Simon also wrote the hit “Red Rubber Ball” for the Cyrkle. They became pals after Paul fled to England to escape the resounding thud of WEDNESDAY MORNING 3 AM, then un-became pals, thus the non-credit. My guess is it had something to do with publishing money. But from Tolstoy to Tinker Bell, from Berkeley to Carmel, this is just finger-poppin, toe-tappin fun, a bold new direction for our morose heroes. Artie’s harmonies come from outer space.

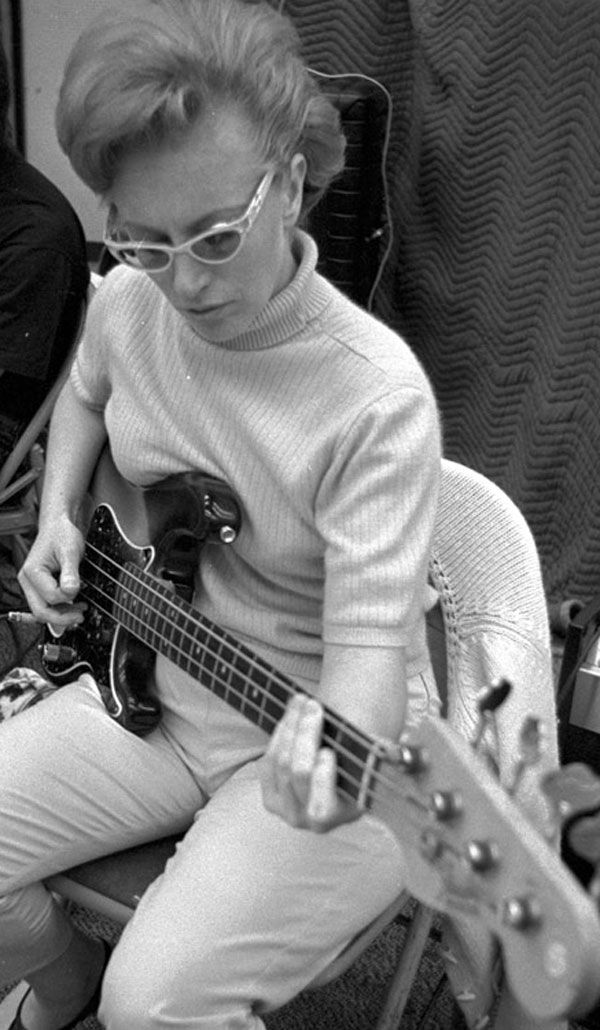

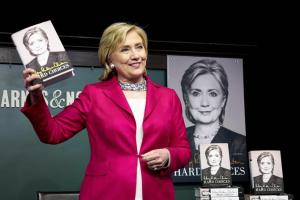

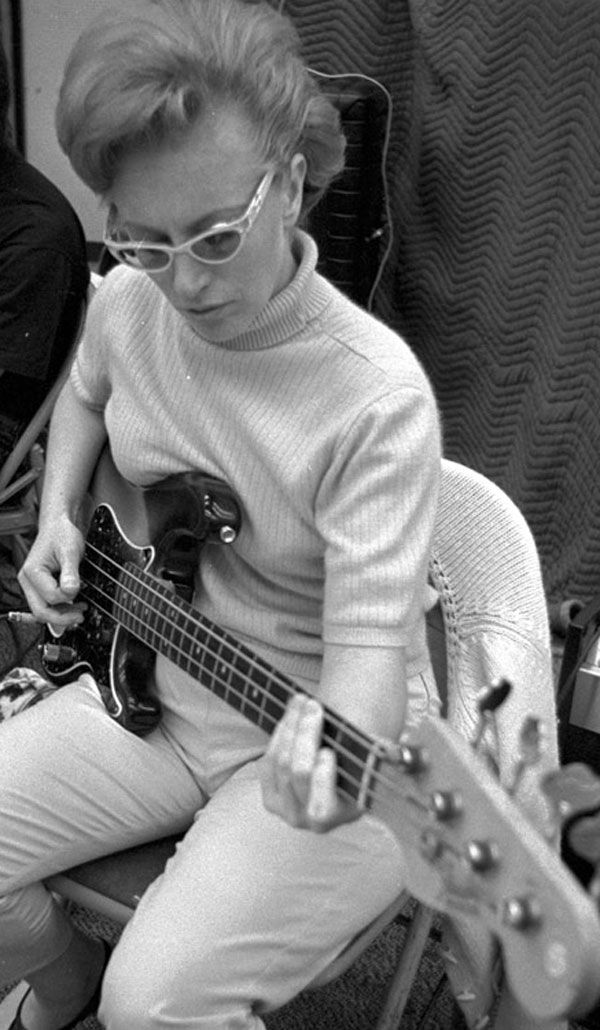

Carol Kaye played bass on both “Scarborough Fair” and “Homeward Bound.”

“Homeward Bound” is one of my favorite songs by anyone, and it sounds every bit as good today as it did when it was fresh. It’s one of the most poignant depictions of life on the road for a touring musician: he and the stand-up comic are the only kinds of performing artists who, when not recording, are traveling all the time. The sheer sameness can throw you off very quickly. I once tagged along with Lynyrd Skynyrd for not quite a week, and one day I woke up in my hotel room, flung open the drapes, and had a mild but real panic attack because I couldn’t suss out where I was until I found a newspaper in the lobby. (This is why rock stars tear up hotel rooms.) But I had no idea when I first heard this song how real it is. Simon probably wrote it in England, since he’s “sittin’ in the railway station” rather than a car or bus. The song is terrific, but the record yells out “hit!” because of Hal Blaine’s muscular beat and Carol Kaye’s bass line. (Yes, among their many other credits, the “Wrecking Crew” of LA session cats blew anonymously for S&G too. Carol also plays on “Scarborough Fair/Canticle.”) I know it’s the arrangement that counts because when the boys do it with Paul as their “one-man band,” it just ain’t the same. Judge for yourself, early in their Central Park concert.

Advertising is crass and manipulative! So avers “The Big Bright Green Pleasure Machine,” which sounds like a certain songwriter might have been watching way too much tv. Still, the banal pitches for the title panacea display wit and economy. “Does your group have more cavities than theirs?” “Do you sleep alone when others sleep in pairs?” There’s even what passes for controversy in 1966: “Are you worried ‘cause your girlfriend’s just a little late?” Not your wife, your girlfriend. You’ve been having extramarital sex, haven’t you? This piece was minor the day it was written and doesn’t age well, but the performance is full-on Everlys.

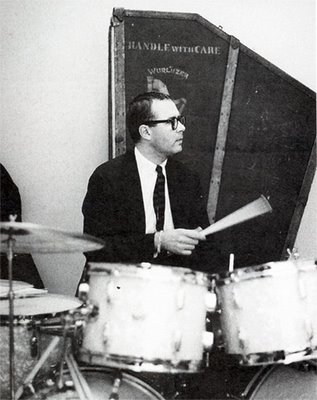

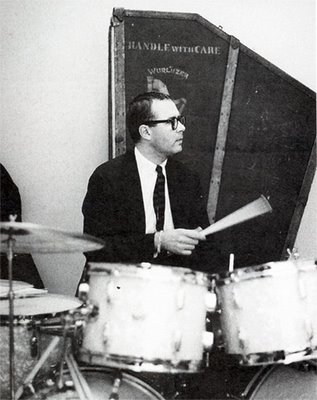

Joe Morello brushed the tubs on “The 59th Street Bridge Song.”

And now, turning on a dime, the happiest 1:43 on record. Without a trace of irony, Simon & Garfunkel go skipping down the street on “The 59th Street Bridge Song (Feelin’ Groovy),” which celebrates that euphoric feeling you get when everything’s perfect or the drugs have just kicked in. “Groovy” as a word has outlived its usefulness (basically replaced by “cool,” which comes from the beatnik era, and “awesome,” which comes from — I dunno, IMAX superhero movies?) but the song’s exalted state is still crystal clear today. Here again, the recording completely sells the exuberance, for the boys have borrowed none other than half of (labelmates) The Dave Brubeck Quartet. Eugene Wright is on upright bass and Joe Morello is swattin’ the super-hip brushes that set the tone immediately; yes, the same guys who recorded the immortal “Take Five.” Veteran S&G fans were nervously waiting for the other shoe to drop, as it had in “Richard Cory,” but no: “Life, I love you / All is groovy.” Angelic la-la syllables dart, weave, spill over each other in a growing chorus of contentment that luxuriously plays us out of side 1. I was happily amazed at first spin, and the song fulfills its simple mission so effectively that it has become timeless despite that antiquated adverb.

“The Dangling Conversation” is about pretension, but it’s pretentious itself, probably why it hasn’t held up as well as S&G’s other big hits. It felt much more profound in 1966 than it does today. In winkily sniffing at detached privilege it becomes guilty of the same offense. There’s certainly much to like, including once again the economy of a gifted songwriter. Simon only needs a few seconds to lay out the shallow vapidity of proper cocktail chitchat: “Can analysis be worthwhile? / Is the theater really dead?” And the lush orchestration, all harps and strings, is sublime — in a sense, just going to the trouble of writing charts and hiring players helps validate Simon & Garfunkel. But it’s hard to listen past the lyrics and enjoy “The Dangling Conversation” on an aural level, because this particular song is all about the lyrics. It only comes to life once, when despair breaks the singer’s chilly composure: “I only kiss your shadow / I cannot feel your hand…” There’s no doubt that it’s a more intellectual way to Stick It To The Man, which is why it fit right in with the times. But fifty years later, I don’t really mind when it’s over.

True fans had already heard “Flowers Never Bend With The Rainfall” on that B-side. The straight-ahead fast picking sounded great, and since I was listening in mono, what I had here was basically that same radio mix from the single. This is one of those songs where it’s easy to mistake the mood. The melody (the same resigned note for a long while on the verses, with Artie handling the changes upstairs) and vibrant tempo could be for a ditty about waiting for a lover to arrive. Instead, leave it to our boys to muse about the inevitability of death, complete with confusion, illusion, dark shadows, tortured sleep, directionless wandering — some fairly grim stuff. If the vocal were in French, you’d never come close to pinning it down lyrically. There is an interesting thought in the chorus: “So I’ll continue to continue to pretend / My life will never end.” We all do that at a young age. But take it from us, kid: you’re gonna die.

On “A Simple Desultory Philippic (Or How I Was Robert McNamara’d Into Submission)” we discover that Paul Simon does have a sense of humor! It’s the musical equivalent of that time he wore a ludicrous turkey suit on SNL and said they had told him, lighten up, you take yourself s-o-o-o-o seriously. Here he flings out cultural references just because they rhyme, from Ayn Rand to Gen. Maxwell Taylor. He’s been Mick Jaggered and “Silver Daggered,” which if you’re not our age you probably don’t recognize as Joan Baez’s signature song early in her career — in other words, Paul lived through all that folk-singer stuff too. But the centerpiece is the moment when he stops everything to do a fairly snarky impression of Bob Dylan, complete with panting in-out harmonica. He has now addressed the elephant in the room. After all, S&G and Dylan shared a label (Columbia) and a producer (Bob Johnston, formerly Tom Wilson). They had included a hokey, halfhearted cover of “The Times They Are A-Changin’” on their first album (the one that tanked), but if Paul or Artie had ever in their lives said A-Anythin’ outside that session, we don’t know about it. For want of a better pigeonhole, both acts were categorized as “folk-rock,” whatever that means, and they didn’t click personally. We know in retrospect that they were worlds apart and evolved even farther away from each other, but we didn’t have any retrospect back then. We have to assume Dylan didn’t mind the ribbing too much because he recorded a self-harmonized “The Boxer” on his possibly heartfelt but definitely delusional SELF PORTRAIT, and many years later he and Paul toured together, even managing to co-perform a tune or two. I saw them at Madison Square Garden: two long sets that were both enjoyable for completely different reasons. Simon, Garfunkel and Laughter. Who’d have imagined that trio? Sue me, but the Dylan thing is still funny.

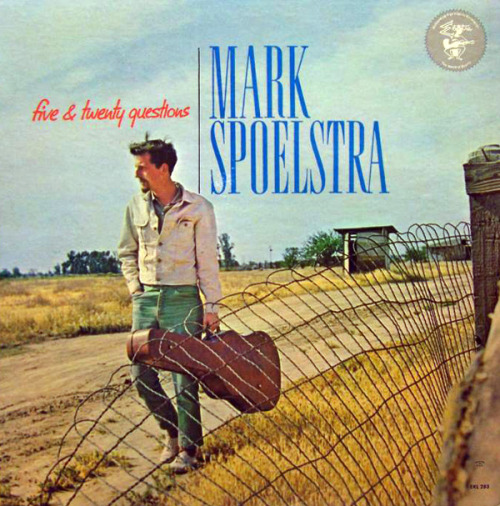

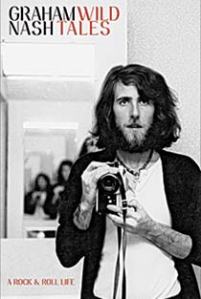

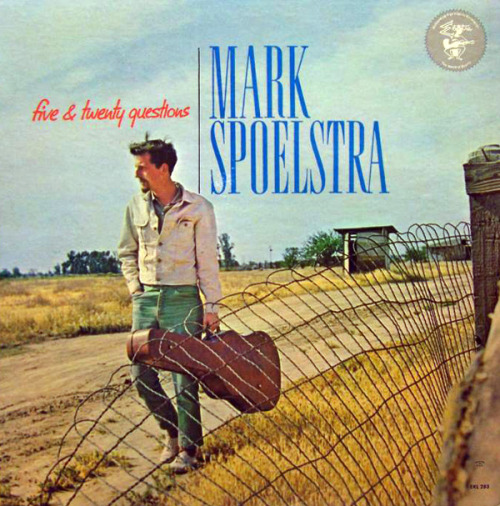

The producers of INSIDE LLEWYN DAVIS aped this Mark Spoelstra cover for the phony album release by “Al Cody” (Adam Driver).

I’ve loved the sound of the 12-string guitar ever since I heard Mark Spoelstra’s FIVE & TWENTY QUESTIONS during the Great Folk Scare. (Roger McGuinn’s Rickenbacker didn’t hurt either.) When you pluck an individual string it sounds double-tracked, like a John Lennon vocal. When you strum them all you have a little guitar orchestra. I finally got next to a Vox Folk Twelve and though it was twice as hard to tune and maintain, I never quit playing it. Paul Simon hits the 12 only rarely, but he does a terrific job on “For Emily, Wherever I May Find Her,” a dreamy solo for Artie that was probably traded off for “Philippic.” Paul’s guitar is mixed in the background and loaded with reverb, and when the lyric says “cathedral bells,” you go, that’s what it sounds like: a cathedral! Talk about puffy shirts: this is Jane Austen set to music, aimed directly at the chicks. Organdy, crinoline, juniper, burgundy, frosted fields, tripping bells, honey hair, flushed cheeks, grateful tears! Is there anything we forgot? Paul steps forward for a regal guitar break and seals the deal: he makes you want your own 12-string.

But as John and Yoko once said, the dream is over. Now a racing heartbeat pulse introduces “A Poem On The Underground Wall,” a little slice of city life that makes us voyeurs while a profane graffitist defaces a subway poster with “a single-worded poem comprised of four letters.” The tempo doesn’t change but it seems to. As the perv nervously waits for his chance, scrawls his “poem” and books it up the stairs to street level, Paul and Artie help the illusion by becoming ever louder and more intense. He gets closer to what seems like an almost sexual release, maybe not even almost, and we feel like we’re watching something we shouldn’t see. Nothing has prepared us for the chugging inevitability of the rhythm. But most disturbing of all, we find ourselves thinking about what it might feel like to wield the “crayon rosary” ourselves. Finally nothing is left but the pulse we started with, and we’re finished, if not shamed.

Well, not quite. The boys wind up with another “Scarborough Fair/Canticle”-style mashup for a closing bookend. “7 O’Clock News/Silent Night” begins with a reverent version of the venerable holiday carol as only these choirboys can warble. It’s beautiful. Then something seems to interfere with your sound system. You’re getting a rogue radio signal from somewhere. Dammit: some newscaster is ruining the song! How is this even possible? You keep listening and the announcer grows louder while your music gets softer. Now you can’t help but pay attention. Martin Luther King may face the National Guard in Cicero, Illinois. Mass murderer Richard Speck is indicted. HUAC investigates war protest. Nixon says opposition to the war works against the country. The news is nothing but bad, and it has finally overpowered “Silent Night.” Of course, all this was deliberate. The effect is quite powerful — in fact, too much so for posterity. “7 O’Clock News” is like a magic trick: the first time you experience it can be mind-blowing, but there’s a reason most magicians don’t repeat illusions for the same audience. Without the element of surprise, you’re only interested in the method, how you were fooled. Well, S&G hired radio DJ Charlie O’Donnell to read actual news items from August 3, 1966 and engineer Roy Halee worked the faders just right. It’s wrenching the first time, but the returns begin to diminish almost immediately. All these years later it’s not only the now-familiar juxtaposition that weakens the piece: the news items themselves are so stale they’re ancient history. I wish this track had been a B-side, or maybe a single for the holiday, so they could have ended PARSLEY, SAGE with something a bit more permanent. But who knew we’d still be listening to it fifty years later?

Sure, it doesn’t all work, and there are other dated moments. But PARSLEY, SAGE, ROSEMARY AND THYME has spun off so much enjoyment over the decades that it’s instructive to consider how long that span of time really is. Fifty years before PARSLEY, SAGE, the biggest hit records, including “O Sole Mio” by Enrico Caruso, “I Love A Piano” by Billy Murray, and ”Ireland Must Be Heaven, For My Mother Came From There” by Charles Harrison, were made with frickin recording horns. Well, that much time and more has now passed for us since S&G’s first groundbreaker. Yet it still has the power to reach out over an eventful half century, to delight, provoke and entertain. Even after buying all that studio time, I’d say Columbia got its money’s worth and then some.

The stunning Richard Avedon portrait for their next album, BOOKENDS.

Posted by Tom Dupree

Posted by Tom Dupree