There are two kinds of people in the world: those who believe the world can be divided into two kinds of people, and those who don’t.

Sorry, my id just jumped out. Down, boy. It’s the pandemic. I’ma start again.

There are two kinds of people in the world: those who, upon seeing an astonishing magical illusion, feel a sense of wonder; and those who, upon seeing the same thing, feel a sense of irritation.

My wife, for example, is a member of the latter group. She just does not enjoy being fooled by a magician. Knowing that what she just saw was impossible, that there’s no such thing as magic, it’s now bugging her. In the back of her mind, she can’t help but try to retain what she and me and thee all know is reality, and the relentless brainworm won’t vamoose. It’s no fun to her, it’s a puzzle she can’t solve. So it’s better all around if she just skips the magic show.

On the other hand, I love magic and am probably the most gullible dude in the room. But in this day and age, nearly every bit of information is addressable, and if you really want to know how that conjuror bested Penn & Teller on their wonderful tv show FOOL US, a little Googling will suffice. I’ll save you some time by giving you the guiding principle behind most every magical illusion capable of baffling you: you have no conception, none, of the lengths to which a magician is willing to go to prepare for a 30-second trick. That might mean hours at the lathe, or hours repeating one-handed shuffles or second-dealing. A sleight-of-hand expert is every bit as much an artist as is a fine violin player, and they get there the same mundane way: practice, practice, practice.

Now, the more you read (or Google) about magic, the nuts and bolts behind venerable illusions, the more disappointed it can make you. If you enjoy the “effect” (that’s the amazing thing the magician seems to be doing), then learning the “method” (that’s the way he achieves this effect in our normal, non-magical world) often reduces the trick. It certainly saps the grandeur and wonder. I constantly duel between my curiosity — I just have to know in certain cases — and the desire to protect my innocence so that the next performer can sock me silly.

Movie crews perform magic all the time. Too much filmed spectacle these days is computer-generated, a little bit cheaty to my mind, but to me almost all the cinema’s great visual effects moments are “floor effects,” or stuff that’s happening in real time, on the stage, on camera. A great example is the “chest-bursting” scene in ALIEN, probably the single most iconic image from that flick. The actual method is a cousin to the “sawing a lady into halves” classic, same principle, any magician would recognize it, but the effect looked so good that it actually shocked some unprepared cast members. You’ve seen a controlled outward explosion to suggest an inward bullet hit thousands of times. But once you understand such methods, now it takes an over-the-top sequence to impress you, like the dozens of “squibs” they taped onto poor James Caan’s body for the toll booth scene in THE GODFATHER.

There are shelves full of books detailing how to perform standard magic tricks, the ABCs of the field. I have two or three of them. Interestingly, I found them all rather boring. Producing a magic effect is exacting and precise, and learning the method has only one salutary effect: you can recognize a professional absolutely nailing it, as when Teller performs Houdini’s “Needles” illusion. But over time I’ve learned that I’d rather let a magician fool me than oppose him.

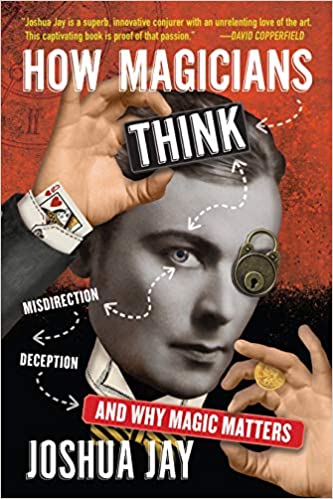

So it was with wide eyes that I read a new book by Joshua Jay called HOW MAGICIANS THINK, confident that it wasn’t going to be a bunch of dry methods (you do learn how exactly one trick was done, thus realizing how your own two eyes can turn you into a chump). This isn’t a book for magicians, but about magicians, and it’s written directly for the layman. If you’re at all curious, I can’t imagine your not liking this one. “Magicians do things beyond our comprehension,” Mr. Jay writes. “When done well, these things should instill in us a unique cocktail of feelings that no other performing art can deliver: escape, awe, and — in the best cases — pure wonder.”

Mr. Jay (no relation to Ricky — whom he cites here as an influence) asks and answers 52 questions, the type you yourself might ask a professional magician over drinks. Do Magicians Get Fooled? What’s Worse — Screwing Up A Trick or Dealing With Hecklers? What Do Magicians Do In Secret? How Do You Build A Magic Show? What’s Your Most Difficult Trick? Why Do Magicians Pull Rabbits Out Of Hats? Who Is The Hardest Audience To Fool? (Spoiler Alert: it’s children.) Is David Blaine For Real? And, of course, Why Do Some People Hate Magic?

The author is a pro but he can’t help writing from the point of view of a fan. He recounts changing his plane schedule to see an amazing Penn & Teller trick a second time; then, without having to face the element of surprise, he was able to glean the method. (He successfully fooled them in season two of their tv show.) We also tag along on his awestruck visit to the world’s greatest museum of magic. It’s located near Las Vegas, it belongs to the avid — and wealthy — magician/collector David Copperfield, and it’s accessible only by personal invitation, five people at a time, each tour personally hosted by the owner. “It’s like seeing Graceland if Elvis were giving the tour,” Mr. Jay sighs.

There is nothing in HOW MAGICIANS THINK that wouldn’t be a legitimate point of conversation at that informal drinks date. There’s no secret code, no instruction-list methods, no arcane esoterica. The book is simply an explication of its title, but it carries a deep resonance in our personal lives. Because knowing how magicians think can help us guard against misdirection and deception, the two main tools of the magician. And of the politician.

Why I have always loved close magic, the sleights? While all magic takes skill, the little stuff right there takes more skill. Big tricks are fun, but that coin vanish right under your nose beats the disappearing elephant every time. I can do a couple sleights, and even when i know exactly what the magician did, I am admiring the real magic of endless practice.

LikeLiked by 1 person