In the early Fifties — the dawn of a Golden Age of advertising, when the new medium of television was jostling recently comfortable postwar, post-Depression families about most everything — a Mad Man named Rosser Reeves came up with a profound theory about how to make tv campaigns effective. He called it the Unique Selling Proposition, and it boils down to this: there is nothing else like our product, therefore you should switch brands to get it.

In the early Fifties — the dawn of a Golden Age of advertising, when the new medium of television was jostling recently comfortable postwar, post-Depression families about most everything — a Mad Man named Rosser Reeves came up with a profound theory about how to make tv campaigns effective. He called it the Unique Selling Proposition, and it boils down to this: there is nothing else like our product, therefore you should switch brands to get it.

So, in ad terms, the hard shell of M&Ms “melts in your mouth, not in your hand” like other gooey chocolate candy does. FedEx delivers overnight “absolutely, positively,” unlike any other carrier. KFC uses a “secret” proprietary recipe; so does Coca-Cola. If your Domino’s ‘za isn’t there in 30 minutes, it’s free. Even staid old Smith Barney made money “the old-fashioned way. We earn it.” Unlike, I guess, those other shysters who only push paper around. These days Reeves’s principle is more commonly known as “positioning,” but that’s just nomenclature. The fact is, the ultimate position in commerce is still the USP: everybody wants it and only we have it.

As others have noted, a political campaign is nothing but an instant business startup that has to go from zero to sixty right away. Donald Trump brought his own USP to the 2016 presidential campaign, and I think it did most of his heavy lifting before he ever opened his mouth. It was a simple, even diabolical position: I am a rich, successful non-politician. That bare statement, plain enough for anyone to comprehend, does a whole lot of subliminal selling.

He’s rich. To be sure, there are other politicians who are also rich. (By a remarkable coincidence, many of them managed to become wealthy even while serving in office!) The subtext is, I’m so rich that I don’t have to worry about special interests, because big shots don’t have the money to push me around: I have a screw-you fortune. (“Special interests” are “powerful entities who don’t donate to me,” just as “outside agitators” are “people who oppose me, no matter where they come from.”) To Americans, great wealth also connotes great worth: that pile of dough has to represent someone’s sweat equity, even if Trump inherited his from Pop, whose initial loan set Young Master Donald on his corporate way. Monarchic subjects worldwide know money can represent nothing more significant than ancestry or blind luck, but we are a nation of rolled-up sleeves and tales of derring-do. To us, rich suggests brave and bold were once up in there too.

But what does “rich” mean? Is it the balance-sheet remainder of one’s assets minus one’s debts? Or is it just a lifestyle choice funded by kicking a gilded can ever farther down the road? There are two widely held harrumphs about Trump’s bottom line. (1) He isn’t as rich as he says he is. (2) It’s paper wealth anyhow, funded by bankruptcy relief, “brand equity” and Scroogelike stiffing of subcontractors and other underlings, and could come tumbling to earth at any time. We can’t evaluate (1) because we are not permitted to see the president’s tax returns, and (2) because the Trumpian empire consists of hundreds of dodgy LLCs (546 to be exact, per a disclosure form filed in May 2016), most of which are trading on a brand name instead of a tactile piece of physical property. The Trump Organization’s largest source of revenue is probably licensing, thus putting the word “Trump” on a par with the Playboy bunny logo. I use the word “probably” with faux Trumplike assurance because I don’t know for sure, and neither do you. The boss wants to keep it that way.

Trump has claimed a net worth of more than $10 billion. (At least his campaign office did, on July 15, 2015.) That number fluctuates over time, but as David Cay Johnston, author of the bio THE MAKING OF DONALD TRUMP, says, “there is not now and never has been any verifiable evidence that Donald Trump is or ever has been a billionaire.” Still, the guy does live in a big-ass tower on Fifth Avenue with his name on it (the White House has basically become his pied-à-terre), so for the sake of argument let’s concede nine-figure “rich.” However, using the president’s own logic, I will state here and now that Trump’s net worth is nowhere near a billion dollars and that’s an absolute true verifiable fact. Now it’s up to him to prove me wrong, and he can’t do it without unzipping his financial fly. So I think I’m on pretty solid ground here when I make my bold, unsubstantiated assertion.

Of course, as the bard of Asbury once observed, “Poor man wanna be rich / Rich man wanna be king / And a king ain’t satisfied / Till he rules everything.” Even if Trump didn’t need other people’s money to bankroll his campaign — he sure didn’t spend much, since he got most of his national exposure for free — homemade bread doesn’t inoculate him from “special interests,” who would very much like to become very much richer on his watch.

He’s successful. Well, at least he’s still around, and he has many possessions. But he’s gone bust often enough to have made “Donald Risk” — that’s what bankers actually call it: yes, the president of the United States has poor credit — unwelcome at U.S. lenders since the mid-Nineties. (Explain to me again how you can lose money running casinos.) This is why people seriously suspect him of having sizable Russian financial obligations. If he needs capital, he has to raise it from somewhere else, and the oligarchs who sacked the Russian state love to park money in real estate. Note that he’s never mentioned Ukraine, either as candidate or president.

But that’s reality. Instead, this guy deals in perception. For more than a decade Donald Trump has played a CEO on television, whose job it is to fire imaginary employees from an imaginary company. This is the image his fans have seen with their own eyes. Of course he’s successful: he’s the big boss! Just ask Gary Busey! One assumes that his “executive producer” position carries a financial piece of THE APPRENTICE along with it. If so, pretense could be more lucrative than actuality. This program, and not real-life business deals, may even have represented Trump’s major source of income these past few years; a hit tv show certainly enriched his boy Steve Bannon for life. But again, I don’t know, and neither do you.

What you do know regarding “successful” is this. If he incurred a $916 million loss that allowed him, through the use of real-estate tax credits, to avoid federal income tax for nearly twenty years, that doesn’t make him smart. It makes him a businessman who lost a billion frickin dollars.

He’s not a politician. This is the crux of the matter. Trump’s pitch is, politicians got us into all these messes, but elect me and I’ll run the country like a business. (Like I do on tv, not like I did in Atlantic City!) But here’s the thing that escapes many patriots: the government isn’t a business.

One of the hoariest chestnuts regularly heard on the campaign trail is, “You balance your family’s budget, don’t you? Why can’t the government balance its budget?” Well, if you own a home or a car, you probably took out a loan to buy it. In other words, you engaged in deficit spending, you owe more than you have, and you haven’t balanced doodly squat. If you drive on a road, stop at a traffic light, call a cop or fireman, drink water that’s not filthy or flammable, or use the many other benefits we take for granted — we haven’t even touched upon soldiers — it takes money to put them there and keep them there. Government does have a purpose. We have to buy some things collectively if we want them at all. Yes, the national debt is onerous, but that’s why we should pay it down when we run a surplus rather than further cut the taxes of bigwigs.

If you equate America — or any nation — to a business, you’re getting some crucial things wrong. To Trump, our relationship to other countries is analogous to the way some CEOs view their competition. It’s a zero-sum conflict: if we win, you lose. That’s not entirely true for businesses like, say, books, which was my last trade. A bestseller lifts all boats. Everybody wants to have Harry Potter at the expense of the competition, sure, but if Potter explodes, that just brings more people into the real or virtual bookstore, and they don’t have to leave with only that. They might buy some books of yours as well.

Now, an auto purchase is a zero-sum game. If you buy a Nissan, you won’t be shopping at a competing dealer for a good little while. All other automakers have lost a sale. But even so, keeping one’s eye on pure profit can be shortsighted. That’s why Henry Ford’s doubling of the minimum wage while he was rolling out Model Ts was so brilliant. He reasoned: if I pay my people more, I’ll be making less on each car, but they can afford to buy cars themselves! We’ll keep making ever more Model Ts, and earn more money in the long run! “The owner, the employees, and the buying public are all one and the same,” quoth Henry, “and unless an industry can so manage itself as to keep wages high and prices low it destroys itself, for otherwise it limits the number of its customers. One’s own employees ought to be one’s own best customers.”

We know that Trump’s worldview is of a shark tank where all nations compete for the chum. He based his whole campaign on that, beginning with Mexico. His travel ban is a piece of theater, since no terrorists from the affected countries have ever threatened the U.S. (Why not ban Saudis, who were the majority of the 9/11 hijackers? Oh yeah, I forgot.) It’s vital for Trump’s pitch to identify a nation-state as the enemy, even though there’s no official policy anywhere to “take American jobs” — capitalism is handling that for itself by buying labor as cheaply as it can, anywhere it can. Official job poaching was Rick Perry’s specialty when he was governor of Texas, but that’s interstate ball.

International relations is not a series of “deals.” It’s the result of centuries of finely hewn agreements and disputes and alliances, most of them based not on inward-looking nationalism but the recognition that we live in an intertwined global society. If we somehow can’t get along politically, at the very least we have to respect one another. For example, there’s one big issue that affects us all. The worst of enemies still share the same planet, and its ecosystem is quickly going nuts. Everybody’s on board except one country, and Trump will almost certainly make our shameful reticence and isolation on climate change even worse.

Any leader of the free world needs a Henry Ford moment. If you help others, that will make life better for you too. As departing longtime diplomat Daniel Fried put it, “We are not an ethno-state, with identity rooted in shared blood. The option of a White Man’s Republic ended at Appomattox. We have, imperfectly, and despite detours and retreat along the way, sought to realize a better world for ourselves and for others, for we understood that our prosperity and our values at home depend on the prosperity and those values being secure as far as possible in a sometimes dark world.”

In contrast, the “America First” viewpoint is very close to Trump’s own personality: look out for Number One. Whip the competition by any means necessary. Renegotiate everything. Break stuff. But Newton’s Third Law applies to politics too. If you suggest abdicating or even reducing U.S. commitment to NATO — yes, everybody should pay their fair share — then Germany has to consider going nuclear for its own protection. If you start banning the immigration of putative “bad dudes,” then the next generation of technologists will locate elsewhere. If you make all undocumented aliens vanish, then your crops will rot in the field.

Trump’s “business experience” consists of overseeing a closely held private family firm, answerable to nobody: not directors, not shareholders. As he has already discovered, the powers of the president are great but not unlimited. Now he’s in charge of a sprawling bureaucracy that won’t necessarily do his bidding. He’s already picked fights with the intelligence community, the judiciary, and his predecessor. Wait till Congress puts its dukes up or Putin finally wipes the smile off his face. The best and worst thing about this amateur is the same: there’s no subtlety. He tweets out what he’s thinking, but at least you know what he’s thinking. Unfortunately, so do his many more businesslike counterparts around the world.

Posted by Tom Dupree

Posted by Tom Dupree

In the early Fifties — the dawn of a Golden Age of advertising, when the new medium of television was jostling recently comfortable postwar, post-Depression families about most everything — a Mad Man named Rosser Reeves came up with a profound theory about how to make tv campaigns effective. He called it the Unique Selling Proposition, and it boils down to this: there is nothing else like our product, therefore you should switch brands to get it.

In the early Fifties — the dawn of a Golden Age of advertising, when the new medium of television was jostling recently comfortable postwar, post-Depression families about most everything — a Mad Man named Rosser Reeves came up with a profound theory about how to make tv campaigns effective. He called it the Unique Selling Proposition, and it boils down to this: there is nothing else like our product, therefore you should switch brands to get it.

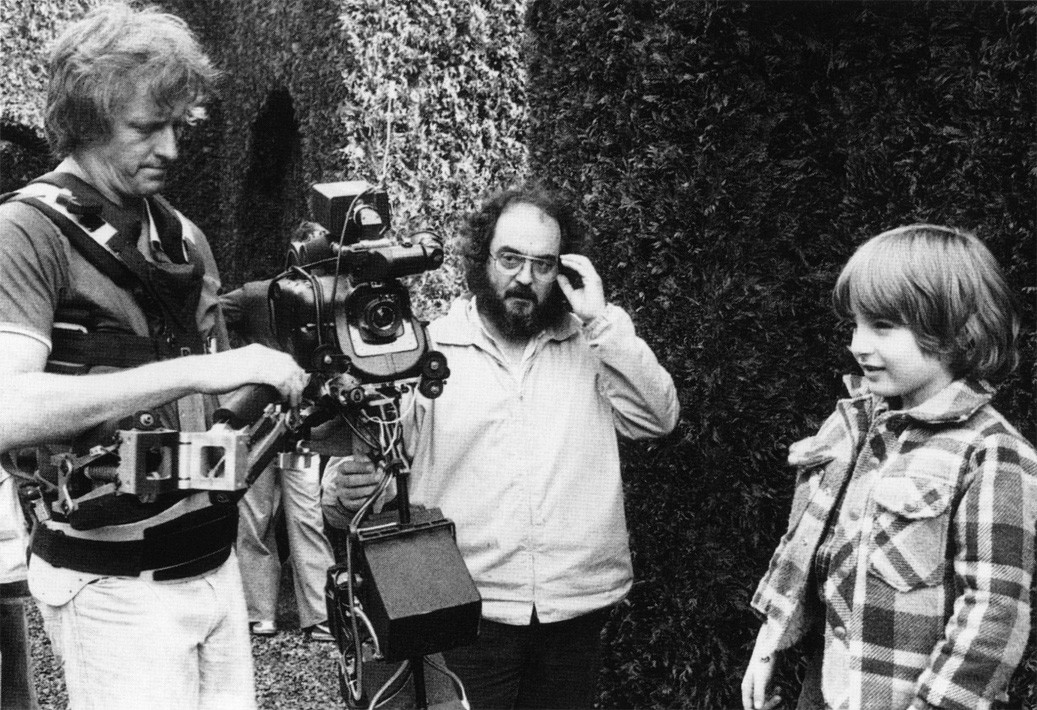

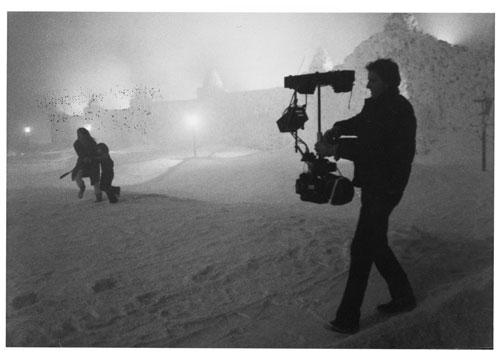

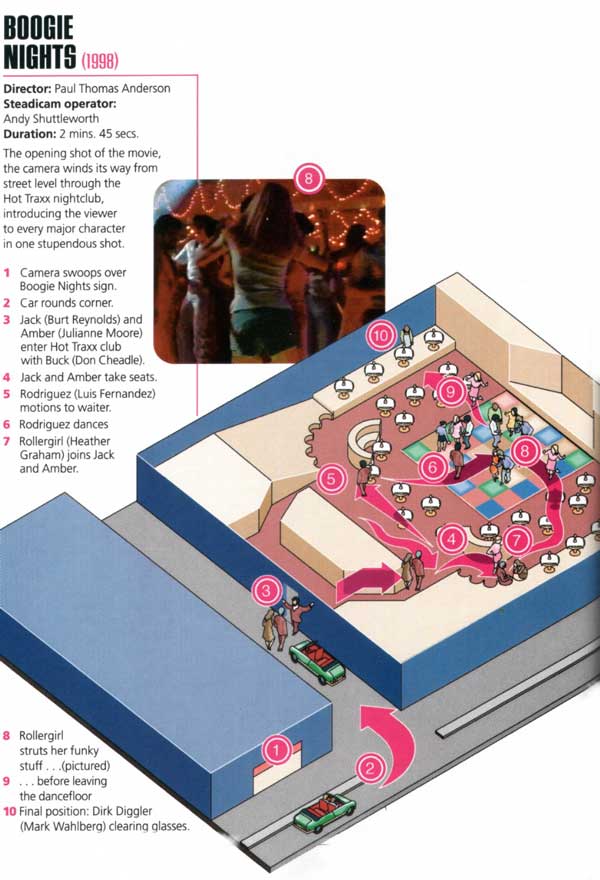

Last year was the 40th anniversary of the Steadicam, which revolutionized filmmaking as much as CGI did a tech generation later. The very first Steadicam shot was realized for Hal Ashby’s Woody Guthrie pic BOUND FOR GLORY (Steadicam shots in MARATHON MAN and ROCKY were filmed later but released earlier), and within a year or so the amazing contraption became available to everybody. Even to us in Mississippi, where I was the first producer in the state to rent a Steadicam, for use in a tv commercial. The leading edge is sometimes the bleeding edge: I wound up wasting money, but I learned a lot in the process.

Last year was the 40th anniversary of the Steadicam, which revolutionized filmmaking as much as CGI did a tech generation later. The very first Steadicam shot was realized for Hal Ashby’s Woody Guthrie pic BOUND FOR GLORY (Steadicam shots in MARATHON MAN and ROCKY were filmed later but released earlier), and within a year or so the amazing contraption became available to everybody. Even to us in Mississippi, where I was the first producer in the state to rent a Steadicam, for use in a tv commercial. The leading edge is sometimes the bleeding edge: I wound up wasting money, but I learned a lot in the process.