So far we’ve been ruminating about the care and feeding of different kinds of authors. How does it work when your author isn’t an author at all? That’s what you face when you enter the land of celebrity books, always one of the hottest aspects of publishing.

I’m not talking here about biography, which doesn’t require the cooperation of the subject. I edited beautiful bios of the writers Terry Southern and Michael O’Donoghue and a haunting account of the parallel lives of Tim Buckley and his son Jeff, and in all three cases we had access to some private material — each of those books is the last word on its subject and will be used as a reference from now on — but no estate had any input into, or approval over, the finished manuscript. What I’m getting at instead is celebrity autobiography, usually by a star of stage, screen, sound or sport, or by a politician who is planning to run for President.

Pop-music autobios have always interested book publishers, nearly all of whom are boomers or later. And just now a notable subset is doing pretty good business: the Summation of the Aging Rock Star. It was probably kicked off by Bob Dylan’s CHRONICLES and Keith Richards’s LIFE, both huge bestsellers and genuinely good books, which have encouraged a host of other musicians (or at least their managers) to crack open the laptop: a month rarely passes without the announcement of another classic-rockin’ book contract.

That’s figurative, of course, the laptop: most celebrity books are co-written by someone who at least has recorded hours of tape, at most researched and reconstructed a life and spit it out in the subject’s voice. The good ones are so good that you can’t tell the difference. They’re credited as “with” or “as told to” in teeny type on the book cover. There’s no shame in that: it doesn’t mean the celebrity is incapable of forming a sentence, only that she became famous for something other than writing a book, and the best way to get an assured voice on the page is to hire a pro. (I heard that Bob Dylan actually wrote his book himself, and there are undoubtedly others who’ve rolled up their sleeves as well. David Byrne’s HOW MUSIC WORKS isn’t about his life but his art, yet it sure feels like it comes straight from the horse’s mouth.) There are also people who have celebrity thrust upon them, like Captain Sully Sullenberger, the commercial pilot who safely landed a huge Airbus A320 in the Hudson River in 2009. To write his book, the captain collaborated with a pro — not a “ghost writer,” since Jeffrey Zaslow’s name is right there on the cover. My old friend Bret Witter is making quite a career out of helping “ordinary” people relate their extraordinary narratives; he’s now officially a multiple New York Times bestselling author.

Musicians who write their own material are artistic cousins to authors; they’re firing similar synapses. Actors, on the other hand, and especially sports stars, are confronted with a type of expression that is utterly foreign to them. Their talent isn’t a natural fit with the process of writing a book. In my experience, some have been better than others in bridging the necessary gap. Once my company published a very famous athlete who was confronted with some incendiary comments in his book (you want to make news if possible), and not only did he deny making them, he was also a little too candid when he denied having read his own autobiography. That’s one extreme.

It all comes down to the individual, and one common attribute. When you’re evaluating a celeb proposal, you’re not only trying to predict how much interest there could be out there, you’re also judging the subject’s ability and plausibility as a storyteller. Because that’s the heart of any celebrity autobio, and here’s where actors regain some advantage, particularly those who’ve enjoyed long careers. It is the rare actor indeed who isn’t also a raconteur. If you can get that delightful quality on paper, you’re in for some fun.

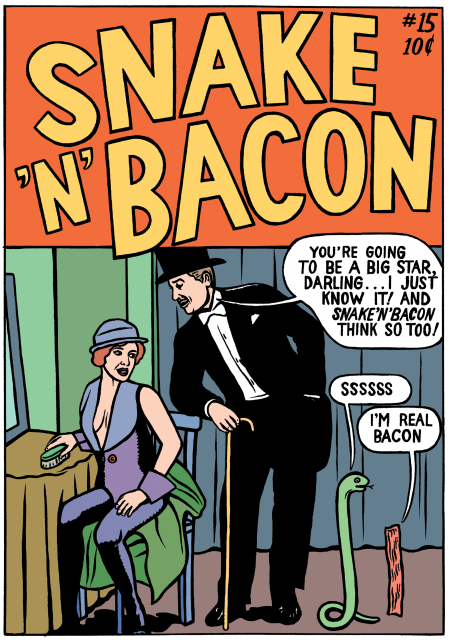

It helps if you yourself enjoy the subject’s work, though you normally can’t go so far as to persuade her to do a book (I made a pest of myself trying to talk the Lucasfilm folks into asking George Lucas to consider an autobio in his own voice. Wouldn’t you like to read that?). The already-assembled package usually lands on your desk through an agent, who is shopping the personality as much as the proposal. Which isn’t to say that you can’t sometimes generate a book on your own. In the mid-Nineties we kept seeing hilarious, so-retro-they’re-hip cartoons by one “P. Revess” in places like the (late, lamented) Oxford American. I made a few calls, searched on this new Internets thing, and tracked down Michael Kupperman in my very own New York. I called him up out of the blue and asked him if he might consider doing a collection of his work, along with some new material. At first (he later told me) Mike suspected it was a prank call. I invited him down to the office to establish my bona fides, and a year or so later we published SNAKE ’N’ BACON’S CARTOON CABARET; in a sense, it’s his autobio. No agent was involved, by the way. I’ve published two other books sans agency, but in all three cases I knew the authors’ work-ethics very well (one reason to have an agent), and each time I proved worthy of their trust by doing everything I promised I would, so they didn’t need protection from me (the other reason). Mike has since gone on to greater things, including a cover illustration for Fortune and many inside illos in The New Yorker and elsewhere, and he’s seen some of his work animated for television. Last year he won the Eisner Award, the Oscar of the comics industry. I didn’t discover Michael Kupperman: those magazine editors did that. But by God, I published his first book, which introduced him to Robert Smigel, who brought his stuff to tv…

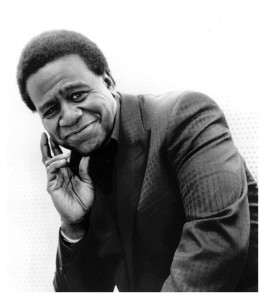

As I said, it helps if you’re a fan. Some celeb books are bought because somebody at the publishing house wanted to hang out with the notable, and that can be tremendous (if expensive) fun. I “inherited” (see Part III) the autobio of the incomparable Al Green when I got to Avon Books, and upon putting it together after heroic work by Al’s co-author Davin Seay, there finally came that wonderful moment when the finished books showed up and the angels sang. Al (or “Reverend,” which is what everybody in his entourage calls him) came to New York to meet with us, do a signing or two, and headline a Central Park concert opened by Odetta. (!) I’d ridden in Rev’s limo to take him to to lunch and then the book signing; we talked about Memphis and music, it was an out-of-body experience in that I remember thinking how lucky I was while words were still coming out of my mouth. Rev invited me to bring my wife backstage before the concert, and we found his trailer just before Odetta went on. He hugged me like I was a long-lost brother (he’d met me only the day before), and after kissing my wife’s hand, he looked deeply into her eyes and said, “Tonight, I’m going to sing ‘Simply Beautiful’ for you.” As we were strolling away toward our seats, Linda noted, I realize that was probably the five millionth time he’s used that line, but my knees still got a little wobbly. I have never met a more adept, more piercing, more sex-exuding, let’s say ladies’ man, than the Rev. Ever. And it only happened because I happened to be a book editor. That’s what I mean: to enter such a milieu, book publishers fight for celebrities.

You may be a fan, yes, but as an editor you have to play dumb. Any celebrity autobio has to be understandable to a reader who’s never heard of the author. You can’t assume the reader knows about the time her boyfriend did that thing, or the day they got thrown out of that hotel. You can’t assume anything; the subject’s life should be understandable to a Martian. (Besides, if the reader knew everything, why in the world would he need to buy your book?) The exception that proves the rule is, you guessed it, Bob Dylan. His highly enjoyable CHRONICLES begins in medias res and jumps around in time, fitting his mercurial, iconoclastic nature perfectly. Some find it excruciating to make the leap. When I was at Bantam, we’d held the contract on Hugh Hefner’s mega-late autobio (wouldn’t you like to read that?) for many years, then one day the accountants said: time to clean house, cancel the contracts that are just fairy tales and get our money back. At Avon, we had a deal with Todd Rundgren to do the most amazingly creative autobio I’ve ever imagined. Upon inheriting the project, I was so reluctant to jettison it that I invited Todd up to the office to see if he was still serious. He showed up and said he was. But I think his creative eyes were bigger than his creative stomach, because he couldn’t make any progress and we had to cancel, me sobbing all the while. (It would have required die-cuts, a different kind of press run…don’t get me started!)

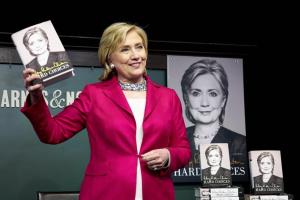

One intangible which you frequently only discover on the fly is, how active will the celebrity be in promoting the book come crunch time? With a politician or a notable who is pushing a particular social issue, well, as the old saying goes, the most dangerous place you can be in Washington is between [POLITICIAN’S NAME] and a camera. (Conservative gasbags are having fun piling on Hillary Clinton right now, but Henry Kissinger — who, it’s safe to say, is not running for President — has been nearly as ubiquitous promoting his new book.) And book publicists, who usually spend too much of their day hearing the word no, enjoy finding themselves able to apportion appearances by their famous temporary clients. But artists and athletes have such a range of personalities that sometimes a guaranteed number of signings or tv appearances becomes a contractual deal point. No promote, no check. I’ve noted reluctance in some celebrity authors (interestingly, never directed at their fans), but then there were people like Richie Havens who not only played music at his signings, but also lunched with booksellers and spent hours autographing books and posters for key accounts. That’s another extreme.

Booksellers, especially staunch independents (of which there are never enough, my friends), are sometimes ambivalent about celebrity publishing. Does a wall full of gold records give this “author” any right to the hallowed lectern occupied last week by Margaret Atwood? Most of these people have never set foot in my store before and never will again! But as I say to anyone who’ll listen, anything that causes anybody to enter a bookstore is good for everybody, whether the come-hither attraction was Jorge Luis Borges or David Lee Roth or Kathie Lee Gifford. A rising tide lifts all bookselling boats, in a bit of cultural magic most recently performed by young Master Harry Potter. All true book professionals are pleased (ok, maybe a tad jealous too) when anything becomes a huge hit, because it brings in customers all set to read something and eventually inquire about something else. The unfortunate part is that a year or two after any trend establishes itself, all the lesser pretenders show up, just as in movies and tv. Where books are concerned, I think the paranormal teens have just about worn themselves out in favor of the ordeals of Hungry Divergent teens, but, as noted, right on cue, here come the geezer rockers to make their grandparents happy!

Publishers guarantee too much for celeb autobios because they bid against each other and it often boils down to, which house employs the biggest fan? You have to get your money back quickly because every year the notable’s career continues puts your book that much farther out of date, and only a well-researched, dispassionate biography can stick around long enough to strike gold on the backlist. Why are there so many serious bios about dead people? Hmmmm. Very few autobiographies can stand the test of time, and the ones that can damn sure don’t come from the entertainment field. But try not to begrudge the “author” who never picked up a book when s/he was in school. Maybe it’s nothing more than time for a little literary payback.

NEXT: Some final thoughts as our Adventures In Editing conclude.

Previous Adventures:

Posted by Tom Dupree

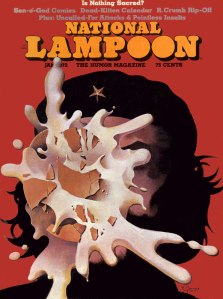

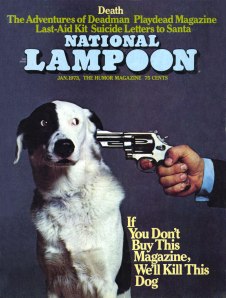

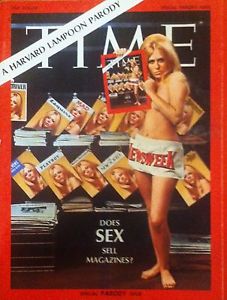

Posted by Tom Dupree  This was my first experience with two of the funniest guys ever to grace the Castle, home of the world’s oldest humor magazine:

This was my first experience with two of the funniest guys ever to grace the Castle, home of the world’s oldest humor magazine: